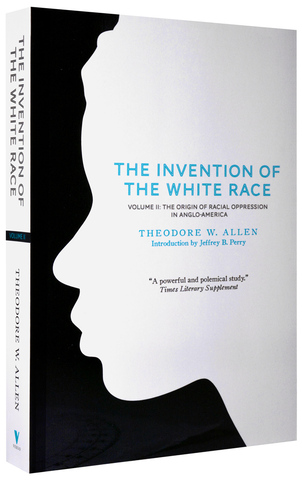

The Invention of the White Race Vol. 2

For those interested in probing Theodore W. Allen'sThe Invention of the White Race Volume 2: The Origin of Racial Oppression in Anglo America, The Expanded Index (Draft, vol. 2, part 1) may prove useful. More of the expanded indexing for these important volumes will follow.

INDEX

[Vol. II of “The Invention of the White Race”]

1 Edw. VI 3 (1547) Vagrancy Act of 1547 20-23

5 & 6 Edw. VI 5 (1551) Tillage 283n18

43 Eliz. 2, (1601) Poor Law: as social control 24-6; right to pay and to leave employment 26

Abbot, Elizabeth 96

Abolition: abolitionist movement 280n66; of slavery 237, 253

absentee landlords 299nn 59-61

Accomack County 157, 161, 166, 180, 335n22: plot 155, 327n51

“Act concerning Servants and Slaves” (1705) 250-1: and establishment of racial oppression and “white race” 272-4; as ruling class manipulation 253

Act “directing the trial of Slaves . . . and for the better government of Negroes, Mulattos, and Indians bond or free” (1723) 241-2, 250-1

Act of Union of England and Scotland (1707) 349n2

Act repealing ban on slavery in Georgia (1750) 253

Adams, William 156

“Address from the People of Ireland to Their Countrymen and Countrywomen in America”

admiralty-type case 180

adulterie/adultery 129, 288n91, 318nn 85, 89

Adventurers 53-4, 63-4, 109, 206, 299n60

African-American bond-laborers: abuse of 141, 323nn 183, 188; arrivals without indentures 179; in Bacon’s Rebellion, joint struggle with European-American bond-laborers for freedom 211, 248, 346n93, not motivated by anti-Indian interests 330n23; barter by 322n167; bastardy laws and 134; collaboration with European-American bond-laborers in actions against their bondage 148-162, 188, readiness to make common cause 161; colonists fear of, uniting with Indians 42; denied right to bear arms 199; direct action with others by running away 188; Elizabeth Key case 194-9; evangelical questions and objections 191-2; John Punch case 178-80; lifetime chattel bond-servitude imposed on, preceded by chattel bond-servitude of European-Americans 300n67; livestock confiscated 250; marriage and freedom 318n77; Maryland slave-owners deliberately foster marriage of male, to European-American women 134, 320n126; number 123-4, 211, 316n40; plots to escape 219, (1722) 242; preamble to South Carolina slave law 293n72; pressure to reduce to lifetime hereditary bond-servitude 123-4, 187-8, challenged 180, 188-91; prohibition from setting free 249, 359n61; punishment for running away 187; rebelliousness of 340n118, 223; in skilled positions 354n97; some owners encourage social mobility and expiration of servitude 193; threat of alliance with French 340n121; time added as penalty 311n37; Virginia-born 123-4; Washburn ignores 340n4; “white identity” and keeping down 249

African-Americans: as buyers and sellers, 181; barred from bearing witness 250; in center of economic history of the hemisphere 9; buy-outs of bond-laborers 188-9; challenge hereditary bondage 188-91; class character of 148; in court 180; contracts made 180-1; in contracts and wills 187-8; denial of rights 250-1; denial of social mobility 279; denied presumption of liberty extended to “white persons and native American Indians” 316n39; denial of testamentary rights 249, 359-60n62; establish normal social status 182; excluded from militia 250; forbidden from holding weapon 250; exclusion of as corollary of “white” identity 249; forbidden from owning Christians 250, from owning “horses, cattle, and hoggs” 287n84; free African-Americans excluded from trades 354n97; free, women declared tithable 187, 190, 250, 336n40; gun licenses 360n74; intermarriage with European-Americans 336n40; importation of bond-laborers 183; laborers 148-149; laborers rights undercut 339n103; landholding, historical significance of 182-6; law against free female, “most explicitly anticipates racial oppression” 187; letter from an African-American, 240; loss of voting rights 242; normal social standing 180-2; not motivated by anti-Indian sentiment in Bacon’s Rebellion 205, 330n23; opposition by propertied class to racial oppression of 193-6; as owners of European-American bond-laborers 186-87; plots 219; prohibited from buying Christian bond-laborers 198; racial oppression in laws against free 250; relative social status of 177-9, “indeterminate” 178; servitude for marriage to European-American 287n84; significant landholding of, in 17th century 182; social mobility of, incompatible with racial oppression 181-2, 186; in trades 354n97; Virginia seeks “to fix a perpetual brand on Free Negros & Mulattos” (Gooch) 242

African bond-laborers: in the Americas 279n58; attempt to establish free settlement at head of James River 245; in Barbados 38; in British West Indies 38-9; discrimination against in skilled occupations 240; Dutch as principal merchants buying and selling (1630s) 310-11n35; English become preeminent suppliers (in 18th century) of 171; Las Casas regrets role in Asiento 4, 277n8; lifetime bond-laborers elsewhere 178-9; in Europe 279n48; number of 8, 198-9, 218, 279nn 48, 58; rebellions 218, 224-5, 240, 352n46, 339n116; social control and 198-9, 224-5, 228-9; status of 177-90; West Africa labor exporting regions of 332n53

African laborers: imported children of African ancestry, age tithable 320n121; shift to, as main supply 240; trade in, as self-motivating capital interest 172; from West Africa; 198, 332n53, 356n9. See also African bond-laborers

Africans: allying with Indians 261; ancestry and headrights 314n4; and intermediate stratum 226, 228; population in Europe 8; prohibitions against working in skilled occupations in English plantation colonies in Americas 240, in Barbados 229; purchased by British army for military service in West Indies 354n108; rebelliousness of newly arriving 356n12; resistance 9, 280n63; as source of labor 8; to Sªo Tomé 277n11. See also African bond-laborers, African laborers

Afro-Brazilians 34, 261-2

Afro-Caribbeans: at first excluded from skilled occupations 233; bond-laborers struggle and “free colored” demands for full citizenship after Haitian Revolution lead to Emancipation 238; bond-laborers who enter British army (after 1807) become free 235; difference of status between persons of African descent in Anglo-America and in the Anglo-Caribbean 238; every concession to freedmen eroded rationale for white supremacy 237; “free blacks and coloreds” in Jamaica own 70,000 of 310,000 bond-laborers 234-5; free colored as shopkeepers and slave-owners 234; free homesteads offered to “every free mulatto, Indian or Negro” in Jamaica 234-5; free persons of color in Jamaica 36% in 1789 and 72% in 1834, in Barbados lower 233; majorities in the British West Indies 232-4; normal class differentiation 234; parallels with Irish struggles against religio-racial oppression 238; petite bourgeois and capitalists sprouted through walls of “white” exclusionism 234; Pinckard argues for social promotion of “people of colour” 236; Rev. Ramsay proposes promoting mulattos as intermediate buffer social control stratum 236; ruling class insights on concessions to freedmen and control over bond-laborers 235-7; traded for enslaved Indians shipped to West Indies 41

agrarian revolution 286n71

Read More

INDEX

[Vol. II of “The Invention of the White Race”]

1 Edw. VI 3 (1547) Vagrancy Act of 1547 20-23

5 & 6 Edw. VI 5 (1551) Tillage 283n18

43 Eliz. 2, (1601) Poor Law: as social control 24-6; right to pay and to leave employment 26

Abbot, Elizabeth 96

Abolition: abolitionist movement 280n66; of slavery 237, 253

absentee landlords 299nn 59-61

Accomack County 157, 161, 166, 180, 335n22: plot 155, 327n51

“Act concerning Servants and Slaves” (1705) 250-1: and establishment of racial oppression and “white race” 272-4; as ruling class manipulation 253

Act “directing the trial of Slaves . . . and for the better government of Negroes, Mulattos, and Indians bond or free” (1723) 241-2, 250-1

Act of Union of England and Scotland (1707) 349n2

Act repealing ban on slavery in Georgia (1750) 253

Adams, William 156

“Address from the People of Ireland to Their Countrymen and Countrywomen in America”

admiralty-type case 180

adulterie/adultery 129, 288n91, 318nn 85, 89

Adventurers 53-4, 63-4, 109, 206, 299n60

African-American bond-laborers: abuse of 141, 323nn 183, 188; arrivals without indentures 179; in Bacon’s Rebellion, joint struggle with European-American bond-laborers for freedom 211, 248, 346n93, not motivated by anti-Indian interests 330n23; barter by 322n167; bastardy laws and 134; collaboration with European-American bond-laborers in actions against their bondage 148-162, 188, readiness to make common cause 161; colonists fear of, uniting with Indians 42; denied right to bear arms 199; direct action with others by running away 188; Elizabeth Key case 194-9; evangelical questions and objections 191-2; John Punch case 178-80; lifetime chattel bond-servitude imposed on, preceded by chattel bond-servitude of European-Americans 300n67; livestock confiscated 250; marriage and freedom 318n77; Maryland slave-owners deliberately foster marriage of male, to European-American women 134, 320n126; number 123-4, 211, 316n40; plots to escape 219, (1722) 242; preamble to South Carolina slave law 293n72; pressure to reduce to lifetime hereditary bond-servitude 123-4, 187-8, challenged 180, 188-91; prohibition from setting free 249, 359n61; punishment for running away 187; rebelliousness of 340n118, 223; in skilled positions 354n97; some owners encourage social mobility and expiration of servitude 193; threat of alliance with French 340n121; time added as penalty 311n37; Virginia-born 123-4; Washburn ignores 340n4; “white identity” and keeping down 249

African-Americans: as buyers and sellers, 181; barred from bearing witness 250; in center of economic history of the hemisphere 9; buy-outs of bond-laborers 188-9; challenge hereditary bondage 188-91; class character of 148; in court 180; contracts made 180-1; in contracts and wills 187-8; denial of rights 250-1; denial of social mobility 279; denied presumption of liberty extended to “white persons and native American Indians” 316n39; denial of testamentary rights 249, 359-60n62; establish normal social status 182; excluded from militia 250; forbidden from holding weapon 250; exclusion of as corollary of “white” identity 249; forbidden from owning Christians 250, from owning “horses, cattle, and hoggs” 287n84; free African-Americans excluded from trades 354n97; free, women declared tithable 187, 190, 250, 336n40; gun licenses 360n74; intermarriage with European-Americans 336n40; importation of bond-laborers 183; laborers 148-149; laborers rights undercut 339n103; landholding, historical significance of 182-6; law against free female, “most explicitly anticipates racial oppression” 187; letter from an African-American, 240; loss of voting rights 242; normal social standing 180-2; not motivated by anti-Indian sentiment in Bacon’s Rebellion 205, 330n23; opposition by propertied class to racial oppression of 193-6; as owners of European-American bond-laborers 186-87; plots 219; prohibited from buying Christian bond-laborers 198; racial oppression in laws against free 250; relative social status of 177-9, “indeterminate” 178; servitude for marriage to European-American 287n84; significant landholding of, in 17th century 182; social mobility of, incompatible with racial oppression 181-2, 186; in trades 354n97; Virginia seeks “to fix a perpetual brand on Free Negros & Mulattos” (Gooch) 242

African bond-laborers: in the Americas 279n58; attempt to establish free settlement at head of James River 245; in Barbados 38; in British West Indies 38-9; discrimination against in skilled occupations 240; Dutch as principal merchants buying and selling (1630s) 310-11n35; English become preeminent suppliers (in 18th century) of 171; Las Casas regrets role in Asiento 4, 277n8; lifetime bond-laborers elsewhere 178-9; in Europe 279n48; number of 8, 198-9, 218, 279nn 48, 58; rebellions 218, 224-5, 240, 352n46, 339n116; social control and 198-9, 224-5, 228-9; status of 177-90; West Africa labor exporting regions of 332n53

African laborers: imported children of African ancestry, age tithable 320n121; shift to, as main supply 240; trade in, as self-motivating capital interest 172; from West Africa; 198, 332n53, 356n9. See also African bond-laborers

Africans: allying with Indians 261; ancestry and headrights 314n4; and intermediate stratum 226, 228; population in Europe 8; prohibitions against working in skilled occupations in English plantation colonies in Americas 240, in Barbados 229; purchased by British army for military service in West Indies 354n108; rebelliousness of newly arriving 356n12; resistance 9, 280n63; as source of labor 8; to Sªo Tomé 277n11. See also African bond-laborers, African laborers

Afro-Brazilians 34, 261-2

Afro-Caribbeans: at first excluded from skilled occupations 233; bond-laborers struggle and “free colored” demands for full citizenship after Haitian Revolution lead to Emancipation 238; bond-laborers who enter British army (after 1807) become free 235; difference of status between persons of African descent in Anglo-America and in the Anglo-Caribbean 238; every concession to freedmen eroded rationale for white supremacy 237; “free blacks and coloreds” in Jamaica own 70,000 of 310,000 bond-laborers 234-5; free colored as shopkeepers and slave-owners 234; free homesteads offered to “every free mulatto, Indian or Negro” in Jamaica 234-5; free persons of color in Jamaica 36% in 1789 and 72% in 1834, in Barbados lower 233; majorities in the British West Indies 232-4; normal class differentiation 234; parallels with Irish struggles against religio-racial oppression 238; petite bourgeois and capitalists sprouted through walls of “white” exclusionism 234; Pinckard argues for social promotion of “people of colour” 236; Rev. Ramsay proposes promoting mulattos as intermediate buffer social control stratum 236; ruling class insights on concessions to freedmen and control over bond-laborers 235-7; traded for enslaved Indians shipped to West Indies 41

agrarian revolution 286n71

Read More