Jeffrey B. Perry Blog

December 17th Marks the 91st Anniversary of the Death of Hubert Harrison in 1927

December 16, 2018

December 17th Marks the 91st anniversary of the death of Hubert Harrison in 1927 at age 44. – Please help to spread the word about his important life and work. For writings by and about Hubert Harrison see -- HERE

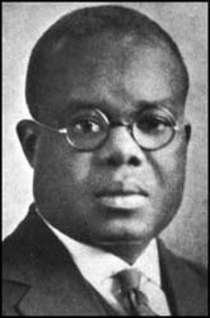

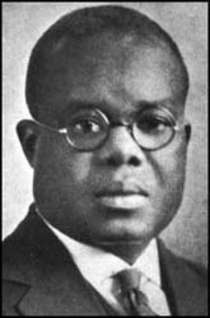

Hubert Harrison (1883-1927) is one of the truly important figures of early twentieth-century America. A brilliant writer, orator, educator, critic, and political activist, he was described by the historian Joel A. Rogers, in "World’s Great Men of Color" as “the foremost Afro-American intellect of his time.” Labor and civil rights leader A. Philip Randolph described Harrison as “the father of Harlem Radicalism.” Harrison’s friend and pallbearer, Arthur Schomburg, fully aware of his popularity, eulogized to the thousands attending Harrison’s Harlem funeral that he was also “ahead of his time.”

Born in St. Croix, Danish West Indies, in 1883, to a Bajan mother and a Crucian father, Harrison arrived in New York as a seventeen-year-old orphan in 1900. He made his mark in the United States by struggling against class and racial oppression, by helping to create a remarkably rich and vibrant intellectual life among African Americans, and by working for the enlightened development of the lives of “the common people.” He consistently emphasized the need for working class people to develop class-consciousness; for “Negroes” to develop race consciousness, self-reliance, and self-respect; and for all those he reached to challenge white supremacy and develop modern, scientific, critical, and independent thought as a means toward liberation.

A self-described “radical internationalist,” Harrison was extremely well-versed in history and events in Africa, Asia, the Mideast, the Americas, and Europe. More than any other political leader of his era, he combined class-consciousness and anti-white supremacist race consciousness in a coherent political radicalism. He opposed capitalism and maintained that white supremacy was central to capitalist rule in the United States. He emphasized that “politically, the Negro is the touchstone of the modern democratic idea”; that “as long as the Color Line exists, all the perfumed protestations of Democracy on the part of the white race” were “downright lying,” that “the cant of ‘Democracy’” was “intended as dust in the eyes of white voters,” and that true democracy and equality for “Negroes” implied “a revolution . . . startling even to think of.”

Working from this theoretical framework, he was active with a wide variety of movements and organizations and played signal roles in the development of what were, up to that time, the largest class radical movement (socialism) and the largest race radical movement (the “New Negro”/Garvey movement) in U.S. history. His ideas on the centrality of the struggle against white supremacy anticipated the profound transformative power of the Civil Rights/Black Liberation struggles of the 1960s and his thoughts on “democracy in America” offer penetrating insights on the limitations and potential of America in the twenty-first century.

Harrison served as the foremost Black organizer, agitator, and theoretician in the Socialist Party of New York during its 1912 heyday; he founded the first organization (the Liberty League) and the first newspaper (The Voice) of the militant, World War I-era “New Negro” movement; and he served as the editor of the “Negro World” and principal radical influence on the Garvey movement during its radical high point in 1920. His views on race and class profoundly influenced a generation of “New Negro” militants including the class radical A. Philip Randolph and the race radical Marcus Garvey. Considered more race conscious than Randolph and more class conscious than Garvey, Harrison is a key ideological link in the two great trends of the Black Liberation Movement -- the labor and civil rights trend associated with Martin Luther King, Jr., and the race and nationalist trend associated with Malcolm X. (Randolph and Garvey were, respectively, the direct links to King marching on Washington, with Randolph at his side, and to Malcolm, whose parents were involved with the Garvey movement, speaking militantly and proudly on street corners in Harlem.)

Harrison was not only a political radical, however. J. A. Rogers described him as an “Intellectual Giant and Free-Lance Educator,” whose contributions were wide-ranging, innovative, and influential. He was an immensely skilled and popular orator and educator who spoke and/or read six languages; a highly praised journalist, critic, and book reviewer (reportedly the first regular book reviewer in “Negro newspaperdom”); a pioneer Black activist in the freethought and birth control movements; a bibliophile and library builder and popularizer who helped develop the 135th Street Public Library into what became known as the internationally famous Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture; a pioneer Black lecturer for the New York City Board of Education and one of its foremost orators). His biography offers profound insights on race, class, religion, immigration, war, democracy, and social change in America.

For information on vol. 1 of the biography of Hubert Harrison see HERE

and see HERE

and also see HERE

Read More

Hubert Harrison (1883-1927) is one of the truly important figures of early twentieth-century America. A brilliant writer, orator, educator, critic, and political activist, he was described by the historian Joel A. Rogers, in "World’s Great Men of Color" as “the foremost Afro-American intellect of his time.” Labor and civil rights leader A. Philip Randolph described Harrison as “the father of Harlem Radicalism.” Harrison’s friend and pallbearer, Arthur Schomburg, fully aware of his popularity, eulogized to the thousands attending Harrison’s Harlem funeral that he was also “ahead of his time.”

Born in St. Croix, Danish West Indies, in 1883, to a Bajan mother and a Crucian father, Harrison arrived in New York as a seventeen-year-old orphan in 1900. He made his mark in the United States by struggling against class and racial oppression, by helping to create a remarkably rich and vibrant intellectual life among African Americans, and by working for the enlightened development of the lives of “the common people.” He consistently emphasized the need for working class people to develop class-consciousness; for “Negroes” to develop race consciousness, self-reliance, and self-respect; and for all those he reached to challenge white supremacy and develop modern, scientific, critical, and independent thought as a means toward liberation.

A self-described “radical internationalist,” Harrison was extremely well-versed in history and events in Africa, Asia, the Mideast, the Americas, and Europe. More than any other political leader of his era, he combined class-consciousness and anti-white supremacist race consciousness in a coherent political radicalism. He opposed capitalism and maintained that white supremacy was central to capitalist rule in the United States. He emphasized that “politically, the Negro is the touchstone of the modern democratic idea”; that “as long as the Color Line exists, all the perfumed protestations of Democracy on the part of the white race” were “downright lying,” that “the cant of ‘Democracy’” was “intended as dust in the eyes of white voters,” and that true democracy and equality for “Negroes” implied “a revolution . . . startling even to think of.”

Working from this theoretical framework, he was active with a wide variety of movements and organizations and played signal roles in the development of what were, up to that time, the largest class radical movement (socialism) and the largest race radical movement (the “New Negro”/Garvey movement) in U.S. history. His ideas on the centrality of the struggle against white supremacy anticipated the profound transformative power of the Civil Rights/Black Liberation struggles of the 1960s and his thoughts on “democracy in America” offer penetrating insights on the limitations and potential of America in the twenty-first century.

Harrison served as the foremost Black organizer, agitator, and theoretician in the Socialist Party of New York during its 1912 heyday; he founded the first organization (the Liberty League) and the first newspaper (The Voice) of the militant, World War I-era “New Negro” movement; and he served as the editor of the “Negro World” and principal radical influence on the Garvey movement during its radical high point in 1920. His views on race and class profoundly influenced a generation of “New Negro” militants including the class radical A. Philip Randolph and the race radical Marcus Garvey. Considered more race conscious than Randolph and more class conscious than Garvey, Harrison is a key ideological link in the two great trends of the Black Liberation Movement -- the labor and civil rights trend associated with Martin Luther King, Jr., and the race and nationalist trend associated with Malcolm X. (Randolph and Garvey were, respectively, the direct links to King marching on Washington, with Randolph at his side, and to Malcolm, whose parents were involved with the Garvey movement, speaking militantly and proudly on street corners in Harlem.)

Harrison was not only a political radical, however. J. A. Rogers described him as an “Intellectual Giant and Free-Lance Educator,” whose contributions were wide-ranging, innovative, and influential. He was an immensely skilled and popular orator and educator who spoke and/or read six languages; a highly praised journalist, critic, and book reviewer (reportedly the first regular book reviewer in “Negro newspaperdom”); a pioneer Black activist in the freethought and birth control movements; a bibliophile and library builder and popularizer who helped develop the 135th Street Public Library into what became known as the internationally famous Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture; a pioneer Black lecturer for the New York City Board of Education and one of its foremost orators). His biography offers profound insights on race, class, religion, immigration, war, democracy, and social change in America.

For information on vol. 1 of the biography of Hubert Harrison see HERE

and see HERE

and also see HERE

Read More

April 27th Marks 135th Anniversary of Birth of Hubert Harrison

April 26, 2018

“Father of Harlem Radicalism” and

Founder of the First Organization and First Newspaper of the Militant “New Negro Movement”

by Jeffrey B. Perry

Hubert H. Harrison (April 27, 1883-December 17, 1927) was a brilliant writer, orator, educator, critic, and radical political activist. Historian Joel A. Rogers, in World’s Great Men of Color, described him as “perhaps the foremost Afro-American intellect of his time.” Civil rights and labor leader A. Philip Randolph, described Harrison as “the father of Harlem Radicalism.” Bibliophile Arthur Schomburg, outstanding collector of materials on people of African descent, eulogized at Harrison’s Harlem funeral that he was “ahead of his time.”

Harrison’s views on race and class profoundly influenced a generation of “New Negro” militants including the class radical A. Philip Randolph and the race radical Marcus Garvey. Considered more race conscious than Randolph and more class conscious than Garvey, Harrison is a key link to two great trends of the Black Liberation Movement – the labor and civil rights trend associated with Martin Luther King, Jr., and the race and nationalist trend associated with Malcolm X. (Randolph and Garvey were important links to King marching on Washington, with Randolph at his side, and to Malcolm (whose father was a Garveyite preacher and whose mother wrote for the “Negro World”), speaking militantly and proudly on street corners in Harlem.

Harrison was not only a political radical, however. Rogers described him as an “Intellectual Giant and Free-Lance Educator,” whose contributions were wide-ranging, innovative, and influential. He was an immensely skilled and popular orator and educator who spoke and/or read six languages; a highly praised journalist, critic, and book reviewer (who reportedly started "the first regular book-review section known to Negro newspaperdom"); a pioneer Black activist in the freethought and birth control movements; and a bibliophile and library builder and popularizer who was an officer on the committee that helped develop the 135th Street Public Library into what has become known as the internationally famous Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture.

Harrison was born on Estate Concordia, St. Croix, Danish West Indies, on April 27, 1883. His mother was an immigrant worker from Barbados and his father, who had been born enslaved in St. Croix, was a plantation worker.

In St. Croix Harrison received the equivalent of a ninth grade education, learned customs rooted in African communal traditions, interacted with immigrant and native-born working people, and grew with an affinity for the poor and with the belief that he was the equal to any other. He also learned of the Crucian people’s rich history of direct-action mass struggles including the successful 1848 enslaved-led emancipation victory; the 1878 island-wide “Great Fireburn” rebellion (in which women such as “Queen Mary” Thomas played prominent roles); and the general strike of October 1879.

After the death of his mother Harrison traveled to New York as a seventeen-year-old orphan in 1900. In his early years in New York he attracted attention as a brilliant high school student, authored over a dozen letters that were published in the New York Times, involved in important African American and Afro-Caribbean working class intellectual circles, and became a freethinker.

In the United States Harrison made his mark by struggling against class and racial oppression, by helping to create a rich and vibrant intellectual life among African Americans, and by working for the enlightened development of the lives of those he affectionately referred to as “the common people.” He consistently emphasized the need for working class people to develop class-consciousness; for “Negroes” to develop race consciousness, self-reliance, and self-respect; and for all those he reached to challenge white supremacy and develop an internationalist spirit and modern, scientific, critical, and independent thought as a means toward liberation.

A self-described “radical internationalist,” Harrison was extremely well-versed in history and events in Africa, the Caribbean, Asia, the Mideast, the Americas, and Europe and he wrote and lectured indoors and out (he was a pioneering soapbox orator) on these topics. More than any other political leader of his era, he combined class-consciousness and anti-white supremacist race consciousness in a coherent political radicalism. He opposed capitalism and imperialism and maintained that white supremacy was central to capitalist rule in the United States. He emphasized that “politically, the Negro is the touchstone of the modern democratic idea”; that “as long as the Color Line exists, all the perfumed protestations of Democracy on the part of the white race” were “downright lying” and “the cant of ‘Democracy’” was “intended as dust in the eyes of white voters”; that true democracy and equality for “Negroes” implied “a revolution . . . startling even to think of”; and that “capitalist imperialism which mercilessly exploits the darker races for its own financial purposes is the enemy which we must combine to fight.”

Working from this theoretical framework, he was active with a wide variety of movements and organizations and played signal roles in the development of what were, up to that time, the largest class radical movement (socialism) and the largest race radical movement (the “New Negro”/Garvey movement) in U.S. history. His ideas on the centrality of the struggle against white supremacy anticipated the profound transformative power of the Civil Rights/Black Liberation struggles of the 1960s and his thoughts on “democracy in America” offer penetrating insights for social change efforts in the twenty-first century.

Harrison served as the foremost Black organizer, agitator, and theoretician in the Socialist Party of New York during its 1912 heyday; spoke at Broad and Wall Streets in front of the New York Stock Exchange in 1912 on socialism for over three hours to an audience that extended as far as his voice could reach (in a clear precursor to “Occupy Wall Street”); was the only Black speaker at the historic Paterson silk workers strike of 1913; founded the first organization (the Liberty League) and the first newspaper (The Voice) of the militant, race-conscious, World War I-era “New Negro” movement and led a giant Harlem rally that protested the white supremacist attacks on the African American community of East St. Louis, Illinois (which is only twelve miles from Ferguson, Missouri) in 1917; edited "The New Negro: A Monthly Magazine of a Different Sort" (“intended as an organ of the international consciousness of the darker races – especially of the Negro race”) in 1919; wrote "The Negro and the Nation" in 1917 and "When Africa Awakes: The 'Inside Story' of the Stirrings and Strivings of the New Negro in the Western World" in 1920; and served as the editor of the Negro World and principal radical influence on the Garvey movement during its radical high point in 1920.

After leaving the "Negro World" and becoming a U.S. citizen in 1922, Harrison wrote and lectured widely. He published in the "Amsterdam News," "Interstate Tattler," "Modern Quarterly," "New Republic," "Nation," "New York Times," "New York Tribune," "Boston Chronicle," "New York World," "Negro Champion," "Opportunity," and the "Pittsburgh Courier." He also lectured for the New York City Board of Education from 1922-1926; served as the New York State Chair of the American Negro Labor Congress and taught World Problems of Race at the Workers (Communist) Party’s Workers’ School and at the Institute for Social Study in Harlem; and spoke at universities, libraries, community forums, and street corners throughout New York City, as well as in New Jersey, Indiana, Illinois, and Massachusetts. Maintaining his political independence, he worked with Democrats, the Single Tax Movement, Virgin Island organizations, the Farmer Labor Party Movement, and Communists. A bibliophile and advocate of free public libraries, he was also a founding officer of the committee that helped develop the “Department of Negro Literature and History” of the 135th Street Public Library into a center for Black studies, subsequently known as the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture. In addition, though he was a trailblazing book reviewer and literary critic during the period known as the Harlem Renaissance, he questioned the “Renaissance” on its willingness to accept standards from “white society” and on its claim to being a rebirth, a claim that he felt ignored the steady flow of works by “Negro” writers since 1850.

In 1924 Harrison founded the International Colored Unity League (ICUL), which emphasized “Negro” solidarity and self-support, advocated “race first” politics, and sought to enfranchise “Negroes” in the South. The ICUL attempted “to do for the Negro the things which the Negro needs to have done without depending upon or waiting for the co-operative action of white people.” It urged that “Negroes” develop “race consciousness” as a defensive measure, be aware of their racial oppression, and use that awareness to unite, organize, and respond as a group. Its economic program advocated cooperative farms, stores, and housing, and its social program included scholarships for youth and opposition to restrictive laws. The ICUL program, described in 1924 talks and newspaper articles and published in "The Voice of the Negro" in 1927, had political, economic, and social planks urging protests, self-reliance, self-sufficiency, and collective action and included as its “central idea” the founding of “a Negro state, not in Africa, as Marcus Garvey would have done, but in the United States” as an outlet for “racial egoism.” It was a plan for “the harnessing” of “Negro energies” and for “economic, political and spiritual self-help and advancement.” It preceded a somewhat similar plan by the Communist International by four years. The journalist and activist Hodge Kirnon from Montserrat was one of the ICUL officers and in 1924 Harrison and Rogers spoke on behalf of the organization in the Midwest and in New England.

In 1927 Harrison edited the International Colored Unity League’s "Embryo of the Voice of The Negro" and then "The Voice of the Negro" until shortly before his unexpected December 17 death at Bellevue Hospital in New York from an appendicitis-related condition. His funeral was attended by thousands and preceded his burial in Woodlawn Cemetery in the Bronx, a gift of his portrait for placement on the main floor of the 135th Street Public Library, and the (ironic) establishment of The Hubert Harrison Memorial Church in Harlem in his honor.

Hubert Harrison lived and died in poverty. In 2015, after eighty-seven years, a beautiful tombstone was placed on his shared and previously unmarked gravesite. His gravesite marker includes his image and words drawn from Andy Razaf, outstanding poet of “New Negro Movement” – speaker, editor, and sage . . . “What a change thy work hath wrought!” That commemorative marker, as well as the notable increase in books, articles, videos, audios, and discussions on his life and work reflect a growing recognition of his importance and indicate that interest in this giant of Black history will continue to grow in the twenty-first century and that Hubert Harrison has much to offer people today.

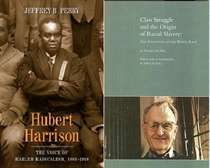

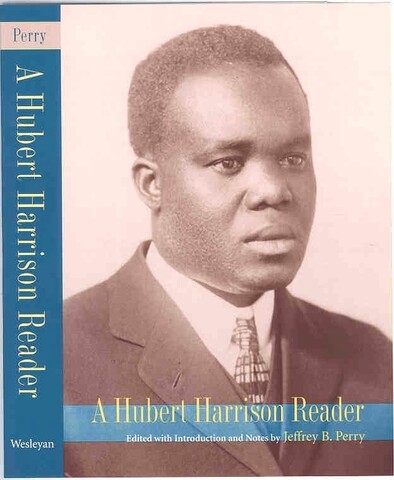

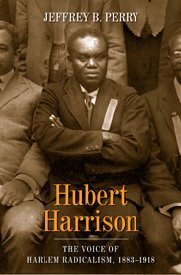

Dr. Jeffrey B. Perry is an independent, working class scholar and archivist who was formally educated at Princeton, Harvard, Rutgers, and Columbia University. He was a long-time rank-and-file activist, elected union officer with Local 300, and editor for the National Postal Mail Handlers Union (div. of LIUNA, AFL-CIO). Perry preserved and inventoried the Hubert H. Harrison Papers (now at Columbia University's Rare Book and Manuscript Library); edited of A Hubert Harrison Reader (Wesleyan University Press, 2001); authored Hubert Harrison: The Voice of Harlem Radicalism, 1883-1918 (Columbia University Press, 2008); wrote the introduction and notes for the new, expanded edition of Hubert H. Harrison, When Africa Awakes: The “Inside Story” of the New Negro in the Western World (1920; Diasporic Africa Pres, 2015); and wrote the new introduction and supplemental material for the expanded edition of Theodore W. Allen, The Invention of the White Race, 2 vols. (1994, 1997; Verso Books, 2012). He is currently working on volume two of the Hubert Harrison biography and preparing his vast collection of Theodore W. Allen Papers and Research Materials on Hubert Harrison for placement at a major repository.

For comments from scholars and activists on "Hubert Harrison: The Voice of Harlem Radicalism, 1883-1918" (Columbia University Press) see HERE

and see HERE

For information on "A Hubert Harrison Reader" (Wesleyan University Press) see HERE

For information on the new, Diasporic Africa Press expanded edition of Hubert H. Harrison's “When Africa Awakes: The 'Inside Story’ of the Stirrings and Strivings of the New Negro in the Western World” see HERE

For a video of a Slide Presentation/Talk on Hubert Harrison see HERE

For articles, audios, and videos by and about Hubert Harrison see HERE

For a link to the Hubert H. Harrison Papers at Columbia University’s Rare Book and Manuscript Library see HERE

Read More

100th Anniversary of Hubert Harrison’s Founding of the First Organization of the Militant “New Negro Movement"

June 12, 2017

of the First Organization of the Militant “New Negro Movement”

One hundred years ago, on June 12, 1917, Hubert Harrison founded the Liberty League of Negro-Americans at a rally attended by thousands at Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church, 52-60 W. 132nd Street in Harlem. It was the first organization of the militant “New Negro Movement.” Several weeks later, on July 4, at a large rally at Metropolitan Baptist Church, 120 W. 138th Street, Harrison founded the movement’s first paper – “The Voice: A Newspaper for the New Negro.”

The Liberty League’s Bethel rally was called around the slogans "Stop Lynching and Disfranchisement” and “Make the South 'Safe For Democracy.'” Listed speakers included Harrison, the young activist Chandler Owen, and Dr. Adam Clayton Powell, Sr. (of Abyssinian Baptist Church). Marcus Garvey, a relatively unknown former printer from Jamaica also spoke at the rally in what was his first talk before a major Harlem audience.

The League's stated purpose was to take steps "to uproot" the twin evils of lynching and disfranchisement and "to petition the government for a redress of grievances." It aimed to "carry on educational and propaganda work among Negroes" and "exercise political pressure wherever possible" in order to "abate lynching." Harrison said it offered "the most startling program of any organization of Negroes in the country" as it demanded democracy at home for "Negro-Americans" before they would be expected to enthuse over democracy in Europe.

Two thousand people packed the Bethel church meeting and the audience rose in support during Harrison's introduction when he demanded "that Congress make lynching a Federal crime." Resolutions were passed calling the government's attention to the continued violation of the thirteenth, fourteenth and fifteenth amendments (regarding slavery and involuntary servitude, citizenship rights, and voting rights); to the existence of mob law from Florida to New York; and to the demand that lynching be made a federal crime. In his talk Harrison also called for retaliatory self-defense whenever Black lives were threatened by mobs.

The Liberty League emphasized "a special sympathy" for “our brethren in Africa" and pledged to "work for the ultimate realization of democracy in Africa -- for the right of these darker millions to rule their own ancestral lands -- even as the people of Europe -- free from the domination of foreign tyrants." The League also adopted a tricolor flag. Harrison explained, because of the "Negro's" "dual relationship to our own and other peoples," we “adopted as our emblem the three colors, black brown and yellow, in perpendicular stripes." These colors were chosen because the "black, brown and yellow, [were] symbolic of the three colors of the Negro race in America." They were also, he suggested, symbolic of people of color worldwide.

Garvey, his fellow Jamaican and future “Negro World” editor W. A. Domingo, and other leading activists, including a number of important future leaders of the Garvey movement, joined Harrison’s Liberty League. From the Liberty League and the Voice came many core progressive ideas later utilized by Garvey in both the Universal Negro Improvement Association and the “Negro World.” Contemporaries readily acknowledged that Harrison’s work laid groundwork for the Garvey movement. Harrison claimed that from the Liberty League “Garvey appropriated every feature that was worthwhile in his movement” and that the secret of Garvey’s success was that he “[held] up to the Negro masses those things which bloom in their hearts” including “race-consciousness” and “racial solidarity” – “things taught first in 1917 by the “Voice” and The Liberty League.”

The July 4 meeting at which “The Voice” appeared came in the wake of the vicious white supremacist attacks (Harrison called it a “pogrom”) on the African American community of East St. Louis, Illinois (which is twelve miles from Ferguson, Missouri). Harrison again advised “Negroes” who faced mob violence in the South and elsewhere to "supply themselves with rifles and fight if necessary, to defend their lives and property." According to the “New York Times” he received great applause when he declared that "the time had come for the Negroes [to] do what white men who were threatened did, look out for themselves, and kill rather than submit to be killed." He was quoted as saying: "We intend to fight if we must . . . for the things dearest to us, for our hearths and homes." In his talk he encouraged “Negroes” everywhere who did not enjoy the protection of the law to arm in self-defense, to hide their arms, and to learn how to use their weapons. He also reportedly called for a collection of money to buy rifles for those who could not obtain them themselves, emphasizing that "Negroes in New York cannot afford to lie down in the face of this" because "East St. Louis touches us too nearly." According to the “Times,” Harrison said it was imperative to "demand justice" and to "make our voices heard." This call for armed self-defense and the desire to have the political voice of the militant New Negro heard were important components of Harrison's militant “New Negro” activism.

The Voice featured Harrison’s outstanding writing and editing and it included important book review and “Poetry for the People” sections. It contributed significantly to the climate leading up to Alain LeRoy Locke’s 1925 publication “The New Negro.”

Beginning in August 1919 Harrison edited “The New Negro: A Monthly Magazine of a Different Sort,” which described itself as “A Magazine for the New Negro,” published “in the interest of the New Negro Manhood Movement,” and “intended as an organ of the international consciousness of the darker races -- especially of the Negro race.”

In early 1920 Harrison assumed "the joint editorship" of the “Negro World” and served as principal editor of that globe-sweeping newspaper of Marcus Garvey’s Universal Negro Improvement Association (which was a major component of the “New Negro Movement”).

Then, in August 1920, while serving as editor of the “Negro World,” Harrison completed “When Africa Awakes: The “Inside Story” of the Stirrings and Strivings of the New Negro in the Western World.” Many of Harrison’s most important “New Negro Movement” editorials and reviews from the 1917-1920 period were reprinted in “When Africa Awakes.” The book, recently republished in expanded form by Diasporic Africa Press, makes clear his pioneering theoretical, educational, and organizational role in the founding and development of the militant “New Negro Movement.”

Brief Biographical Background Pre the Founding of Militant “New Negro Movement”

St. Croix, Virgin Islands-born, Harlem-based, Hubert Henry Harrison (1883-1927) was a brilliant, class conscious and race conscious, writer, educator, orator, editor, book reviewer, political activist, and radical internationalist. Historian J. A. Rogers in “World’s Great Men of Color” described him as an “Intellectual Giant” who was “perhaps the foremost Aframerican intellect of his time.” Labor and civil rights activist A. Philip Randolph, referring to a period when Harlem was considered an international “Negro Mecca” and the “center of radical black thought,” described him as “the father of Harlem radicalism.” Richard B. Moore, active with the Socialist Party, African Blood Brotherhood, Communist Party, and movements for Caribbean independence and federation, described Harrison as “above all” his contemporaries in his steady emphasis that “a vital aim” was “the liberation of the oppressed African and other colonial peoples.”

Hubert Harrison played unique, signal roles in the largest class radical movement (socialism) and the largest race radical movement (the “New Negro”/Garvey movement) of his era. He was a major influence on the class radical Randolph, on the race radical Garvey, and on other militant “New Negroes” in the period around World War I. W. A. Domingo, a socialist and the first editor of Garvey’s “Negro World” newspaper explained, “Garvey like the rest of us [A. Philip Randolph, Chandler Owen, Cyril Briggs, Grace Campbell, Richard B. Moore, and other “New Negroes”] followed Hubert Harrison.” Historian Robert A. Hill refers to Harrison as “the New Negro ideological mentor.” Considered the most class conscious of the race radicals and the most race conscious of the class radicals in those years, he is a key link in the two great trends of the Civil Rights/Black Liberation struggle – the labor and civil rights trend associated with Randolph and Martin Luther King Jr. and the race and nationalist trend associated with Garvey and Malcolm X. (King marched on Washington with Randolph at his side and Malcolm’s father was a Garveyite preacher and his mother was a reporter for Garvey’s Negro World, the newspaper for which Harrison had been principal editor.)

From 1911 to 1914 Harrison served as the leading Black theoretician, speaker, and activist in the Socialist Party of America. Party statements and practices -- including events at the 1912 convention where Socialists failed to address the “Negro Question” and supported Asian exclusion as “legislation restricting the invasion of the white man’s domain by other races” -- caused him to leave the Socialist Party in 1914. After departing, he offered what is arguably the most profound, but least heeded, criticism in the history of the United States left -- that Socialist Party leaders, like organized labor leaders, put the “white race” first, before class, that they put the [“white’] “Race First and class after.”

Harrison was a pioneering Black activist in the Freethought, Free Speech, and Birth Control Movements. Two years after leaving the Socialist Party, Harrison turned to concentrated work in the Black community. Beginning in 1916, he served as the intellectual guiding light of the militant “New Negro Movement” -- the race and class conscious, internationalist, mass based, autonomous, militantly assertive movement for “political equality, social justice, civic opportunity, and economic power.”

Those interested in additional information on Hubert Harrison and the founding of the militant “New Negro Movement” are encouraged to read "Hubert Harrison: The Voice of Harlem Radicalism, 1883-1918" (Columbia University Press), "A Hubert Harrison Reader" (Wesleyan University Press), and the new, expanded, Diasporic Africa Press edition of Hubert H. Harrison's “When Africa Awakes: The 'Inside Story’ of the Stirrings and Strivings of the New Negro in the Western World.”

For information on "Hubert Harrison: The Voice of Harlem Radicalism, 1883-1918" (Columbia University Press) CLICK HERE

and CLICK HERE

For information on "A Hubert Harrison Reader" (Wesleyan University Press) CLICK HERE

For information on the new, expanded, Diasporic Africa Press edition of Hubert H. Harrison's “When Africa Awakes: The 'Inside Story’ of the Stirrings and Strivings of the New Negro in the Western World” CLICK HERE

For a video of a Slide Presentation/Talk on Hubert Harrison at the Dudley Public Library, Roxbury, Mass. filmed by Boston Neighborhood News TV CLICK HERE

For a video of a Slide Presentation/Talk on HUBERT HARRISON the “Father of Harlem Radicalism” for the St. Croix Landmarks Society CLICK HERE (Note: The slides are very clear.)

For articles, audios, and videos by and about Hubert Harrison CLICK HERE

Read More

Hubert Harrison Growing Appreciation for this Giant of Black History December 17 Marks the 89th Anniversary of His Death

December 17, 2016

Hubert Harrison (1883-1927), the “father of Harlem radicalism” and founder of the militant “New Negro Movement,” is a giant of our history. He was extremely important in his day and his significant contributions and influence are attracting increased study and discussion today. On the anniversary of his December 17, 1927, death let us all make a commitment to learn more about the important struggles that he and others waged. Let us also commit to share this knowledge with others.

Harrison was born in St. Croix, Danish West Indies, on April 27, 1883, to a laboring-class Bajan mother and a born-enslaved, plantation-laboring Crucian father. He arrived in New York as a seventeen-year-old orphan in 1900. He made his mark in the United States by struggling against class and racial oppression, by helping to create a remarkably rich and vibrant intellectual life among African Americans and by working for the enlightened development of the lives of those he affectionately referred to as “the common people.” He consistently emphasized the need for working class people to develop class-consciousness; for “Negroes” to develop race consciousness, self-reliance, and self-respect; and for all those he reached to challenge white supremacy and develop an internationalist spirit and modern, scientific, critical, and independent thought as a means toward liberation.

A self-described “radical internationalist,” Harrison was extremely well-versed in history and events in Africa, the Caribbean, Asia, the Mideast, the Americas, and Europe and he wrote voluminously and lectured indoors and out on these topics. More than any other political leader of his era, he combined class-consciousness and anti-white supremacist race consciousness in a coherent political radicalism. He opposed capitalism and imperialism and maintained that white supremacy was central to capitalist rule in the United States. He emphasized that “politically, the Negro is the touchstone of the modern democratic idea”; that “as long as the Color Line exists, all the perfumed protestations of Democracy on the part of the white race” were “downright lying” and “the cant of ‘Democracy’” was “intended as dust in the eyes of white voters”; that true democracy and equality for “Negroes” implied “a revolution . . . startling even to think of,” and that “capitalist imperialism which mercilessly exploits the darker races for its own financial purposes is the enemy which we must combine to fight.”

Working from this theoretical framework, he was active with a wide variety of movements and organizations and played signal roles in the development of what were, up to that time, the largest class radical movement (socialism) and the largest race radical movement (the “New Negro”/Garvey movement) in U.S. history. His ideas on the centrality of the struggle against white supremacy anticipated the profound transformative power of the Civil Rights/Black Liberation struggles of the 1960s and his thoughts on “democracy in America” offer penetrating insights on the limitations and potential of America in the twenty-first century.

Harrison served as the foremost Black organizer, agitator, and theoretician in the Socialist Party of New York during its 1912 heyday; he founded the first organization (the Liberty League) and the first newspaper (The Voice) of the militant, World War I-era “New Negro” movement; edited The New Negro: A Monthly Magazine of a Different Sort (“intended as an organ of the international consciousness of the darker races -- especially of the Negro race”) in 1919; wrote When Africa Awakes: The “Inside Story” of the Stirrings and Strivings of the New Negro in the Western World in 1920; and he served as the editor of the Negro World and principal radical influence on the Garvey movement during its radical high point in 1920.

His views on race and class profoundly influenced a generation of “New Negro” militants including the class radical Randolph and the race radical Garvey. Considered more race conscious than Randolph and more class conscious than Garvey, Harrison is the key link in the ideological unity of the two great trends of the Black Liberation Movement -- the labor and civil rights trend associated with Martin Luther King, Jr., and the race and nationalist trend associated with Malcolm X. (Randolph and Garvey were, respectively, the direct links to King marching on Washington, with Randolph at his side, and to Malcolm (whose father was a Garveyite preacher and whose mother wrote for the Negro World), speaking militantly and proudly on street corners in Harlem.

Harrison was not only a political radical, however. Rogers described him as an “Intellectual Giant and Free-Lance Educator,” whose contributions were wide-ranging, innovative, and influential. He was an immensely skilled self-educated lecturer (for the New York City Board of Education) who spoke and/or read six languages; a highly praised journalist, critic, and book reviewer (who reportedly started "the first regular book-review section known to Negro newspaperdom"); a pioneer Black activist in the freethought and birth control movements; and a bibliophile and library builder and popularizer who was an officer of the committee that helped develop the 135th Street Public Library into what has become known as the internationally famous Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture.

Hubert Harrison was truly extraordinary and people are encouraged to learn about and discuss his life and work and to Keep Alive the Struggles and Memory of this Giant of Black History.

Additional Information

For comments from scholars and activists on Hubert Harrison: The Voice of Harlem Radicalism, 1883-1918" (Columbia University Press) see HERE

and see

HERE

For information on "A Hubert Harrison Reader" (Wesleyan University Press) see HERE

For information on the new, expanded, Diasporic Africa Press edition of Hubert H. Harrison's “When Africa Awakes: The 'Inside Story’ of the Stirrings and Strivings of the New Negro in the Western World” see HERE

For articles, audios, and videos by and about Hubert Harrison see HERE

For a video of a Slide Presentation/Talk on Hubert Harrison at the Dudley Public Library, Roxbury, Mass. filmed by Boston Neighborhood News TV see HERE

For a NEW VIDEO of a Slide Presentation/Talk on HUBERT HARRISON the “Father of Harlem Radicalism” for the St. Croix Landmarks Society see

HERE (Note: The slides are very clear.)

Read More

Recommended Summer Reading Recommended Summer Viewing On Hubert Harrison and Theodore W. Allen

July 3, 2016

Recommended Summer Viewing

On Hubert Harrison

and Theodore W. Allen

Important summer reading and viewing -- The autodidactic, anti-white supremacist, working-class intellectuals Hubert Harrison and Theodore W. Allen are two of the twentieth century’s most important thinkers on race and class. The following readings and videos are recommended:

“A Hubert Harrison Reader” ed. with an introduction and notes by Jeffrey B. Perry (Wesleyan University Press) CLICK HERE

Jeffrey B. Perry, “Hubert Harrison: The Voice of Harlem Radicalism, 1883-1918” (Columbia University Press) CLICK HERE

Hubert H. Harrison, “When Africa Awakes: The ‘Inside Story’ of the Stirrings and Strivings of the New Negro in the Western World,” edited with an introduction and notes by Jeffrey B. Perry (Diasporic Africa Press) CLICK HERE

Jeffrey B. Perry, “The Developing Conjuncture and Some Insights from Hubert Harrison and Theodore W. Allen on the Centrality of the Fight Against White Supremacy” (which offers the fullest treatment of the development of Allen’s thought -- CLICK HERE

Theodore W. Allen, “The Invention of the White Race” Volume 1: “Racial Oppression and Social Control," edited with an introduction and notes by Jeffrey B. Perry (Verso Books), CLICK HERE

Theodore W. Allen, “The Invention of the White Race,” Volume 2: "The Origin of Racial Oppression in Anglo-America," CLICK HERE

“Hubert Harrison,” video of a slide presentation/talk by Jeffrey B. Perry at the Dudley Branch of the Boston Public Library in Roxbury, Massachusetts on February 15, 2014, CLICK HERE

“Theodore W. Allen’s ‘The Invention of the White Race’" by Jeffrey B. Perry at the Brecht Forum in New York City CLICK HERE

“Theodore W. Allen and ‘The Invention of the White Race’” video of 2016 slide presentation/talk by Jeffrey B. Perry at a “Multiracial Organizing Conference” against white supremacy in Greensboro, NC CLICK HERE

Jeffrey B. Perry, “The Developing Conjuncture and Some Insights from Hubert Harrison and Theodore W. Allen on the Centrality of the Fight Against White Supremacy” (which offers the fullest treatment of the development of Allen’s thought) http://www.jeffreybperry.net (at Top Left) or see http://clogic.eserver.org/2010/2010.html

Read More

April 27 is the Birthday of Hubert Harrison Share Information on the Life and Work of This Giant of Black History

April 26, 2016

Share Information on the Life and Work of This Giant of Black History

Hubert Henry Harrison (April 27, 1883–December 17, 1927) was a brilliant, St. Croix, Virgin Islands-born, Harlem-based, working-class, writer, orator, educator, critic, and political activist. Historian Joel A. Rogers in “World’s Great Men of Color” said that the autodidactic Harrison was “perhaps the foremost Afro-American intellect of his time.” A. Philip Randolph called him “the father of Harlem radicalism.”

Harrison was a “radical internationalist” and his views on race and class profoundly influenced a generation of "New Negro" militants including the class radical Randolph and the race radical Marcus Garvey. Considered more race-conscious than Randolph and more class-conscious than Garvey, Harrison is a key link in the two great trends of the Black Liberation Movement -- the labor/civil rights trend associated with Randolph and Martin Luther King, Jr., and the race/nationalist trend associated with Garvey and Malcolm X.

Harrison was the leading Black activist in the Socialist Party of New York during its 1912 heyday and the only Black speaker at the historic Paterson silk workers strike of 1913.

He was an extraordinary soapbox orator and the New York Times described how he spoke at Broad and Wall Streets in front of the New York Stock Exchange on socialism for over three hours to an audience that extended as far as his voice could reach (in a clear precursor to “Occupy Wall Street”).

In 1917 Harrison founded the first organization, the Liberty League, and the first newspaper, The Voice, of the militant "New Negro Movement.” That year he also led a giant Harlem rally that protested the white supremacist “pogrom” on the African American community of East St. Louis, Illinois (which is only twelve miles from Ferguson, Missouri).

In 1919 Harrison edited The New Negro: A Monthly Magazine of a Different Sort (“intended as an organ of the international consciousness of the darker races -- especially of the Negro race”).

In 1920 he served as editor of the "Negro World" and as the principal radical influence on the Marcus Garvey movement. Toward the end of that year he published his second book, When Africa Awakes: The “Inside Story” of the Stirrings and Strivings of the New Negro in the Western World.

People are encouraged to include Hubert Harrison in their readings, study, course lists, and courses and to encourage public, private, and school libraries to include books by and about him in their collections.

For comments from scholars and activists on "Hubert Harrison: The Voice of Harlem Radicalism, 1883-1918" (Columbia University Press) CLICK HERE

For a link to the Hubert H. Harrison Papers at Columbia University’s Rare Book and Manuscript Library CLICK HERE

For articles, audios, and videos by and about Hubert Harrison CLICK HERE

For information on "A Hubert Harrison Reader" (Wesleyan University Press) CLICK HERE

For information on the new, Diasporic Africa Press expanded edition of Hubert H. Harrison's “When Africa Awakes: The 'Inside Story’ of the Stirrings and Strivings of the New Negro in the Western World” CLICK HERE

For a video of a Slide Presentation/Talk on Hubert Harrison CLICK HERE

Read More

Five Books to Consider for Readings on Race and Class in America

April 16, 2016

Jeffrey B. Perry, “Hubert Harrison: The Voice of Harlem Radicalism, 1883-1918” (Columbia University Press, 2008). Also see HERE

Theodore W. Allen, “The Invention of the White Race” Volume I: “Racial Oppression and Social Control" , Edited with an Introduction and Notes by Jeffrey B. Perry (1994, Verso Books, new expanded edition 2012).

Theodore W. Allen, “The Invention of the White Race” Volume II: "The Origin of Racial Oppression in Anglo America", Edited with an Introduction and Notes by Jeffrey B. Perry (1997, Verso Books, new expanded edition 2012).

“A Hubert Harrison Reader”, Edited with an Introduction and Notes by Jeffrey B. Perry (Wesleyan University Press, 2001).

Hubert H. Harrison, “When Africa Awakes: The ‘Inside Story’ of the Stirrings and Strivings of the New Negro in the Western World,” New Expanded Edition, Edited with Introduction and Notes by Jeffrey B. Perry (Diasporic Africa Press, 2015).

The independent, working class intellectuals -- Harrison and Allen – are two of the twentieth century’s most important thinkers on race and class. They have much to offer readers today.

In addition, here are links to videos of slide presentation talks on –

Theodore W. Allen's “The Invention of the White Race” at the Brecht Forum in New York City and on

Hubert Harrison (at the Dudley Public Library in Roxbury, Massachusetts).

Read More

Hubert Harrison founded the first organization and the first newspaper of the militant “New Negro Movement” in 1917 (years before Alain Locke’s “New Negro”)

April 6, 2016

Anyone reading about, discussing, or teaching “The New Negro” is encouraged to include in that effort the new, Diasporic Africa Press expanded edition of Hubert H. Harrison's “When Africa Awakes: The 'Inside Story’ of the Stirrings and Strivings of the New Negro in the Western World.”

Hubert Harrison founded the first organization and the first newspaper of the militant “New Negro Movement” in 1917 (years before Alain Locke’s “New Negro” publication) and this book includes over 50 Harrison articles (with introductions and notes) covering the period from 1917 into 1920 (when he edited Marcus Garvey’s “Negro World"). See HERE

You can also see the book at the Diasporic Africa Press website HERE

See the E-book HERE

Read More

Hubert Harrison, W.E.B. Du Bois, and Theodore W. Allen"The Blindspot"

December 27, 2015

“. . . as long as the Color Line exists, all the perfumed protestations of Democracy on the part of the white race must be simply downright lying . . . The cant of ‘Democracy’ is intended as dust in the eyes of white voters . . . It furnishes bait for the clever statesmen.”

New Negro, 1919

“It is only the Blindspot in the eyes of America, and its historians, that can overlook and misread so clean and encouraging a chapter of human struggle and human uplift.”

Black Reconstruction in America:

An Essay Toward a History of the Part Which Black Folk Played

in the Attempt to Reconstruct Democracy in America, 1860-1880

1935

“All the while their white blindspot prevents them from seeing what we are talking about is . . . the ‘white question,’ the white question of questions - the centrality of the problem of white supremacy and the white-skin privilege which have historically frustrated the struggle for democracy, progress and socialism in the US.”

White Blindspot, 1967

Read More

The Developing Conjuncture and Some Insights from Hubert Harrison and Theodore W. Allen on the Centrality of the Fight Against White Supremacy

June 9, 2014

In recent years the gap between rich and poor in the United States has grown to record proportions while stark racial disparities have persisted and in many instances increased. Millions of poor and working people are suffering and conditions are getting worse, particularly for Black and Latino people. This is happening at a time when the U.S. Census Bureau is predicting that “minorities” will comprise more than half of all children by 2023 and the majority of the population by 2042 and at a time when poor and working people domestically and internationally are showing an increased willingness to protest against exploitation and oppression.

While there are many factors affecting the current situation it is instructive to review some class and racial aspects of the developing conjuncture in the United States and to do so in the context of insights drawn from the lives and work of Hubert H. Harrison (1883-1927) and Theodore W. Allen (1919-2005). Harrison and Allen were working-class intellectual/activists who focused on the centrality of the fight against white supremacy and they are two of the twentieth-century’s most important writers on race and class. In the belief that their work has much to offer scholars, activists, and readers today, this essay presents an introduction to Harrison and Allen followed by a brief look at the developing conjuncture and a lengthier discussion of some insights from their lives and work.

For more see -- "The Developing Conjuncture and Some Insights from Hubert Harrison and Theodore W. Allen on the Centrality of the Fight Against White Supremacy" by Jeffrey B. Perry in Cultural Logic, Special Issue: Culture and Crisis, available HERE and HERE

Read More

While there are many factors affecting the current situation it is instructive to review some class and racial aspects of the developing conjuncture in the United States and to do so in the context of insights drawn from the lives and work of Hubert H. Harrison (1883-1927) and Theodore W. Allen (1919-2005). Harrison and Allen were working-class intellectual/activists who focused on the centrality of the fight against white supremacy and they are two of the twentieth-century’s most important writers on race and class. In the belief that their work has much to offer scholars, activists, and readers today, this essay presents an introduction to Harrison and Allen followed by a brief look at the developing conjuncture and a lengthier discussion of some insights from their lives and work.

For more see -- "The Developing Conjuncture and Some Insights from Hubert Harrison and Theodore W. Allen on the Centrality of the Fight Against White Supremacy" by Jeffrey B. Perry in Cultural Logic, Special Issue: Culture and Crisis, available HERE and HERE

Read More

Who Was Hubert Harrison? Chris Stevenson Interviews Author Jeffrey B. Perry

May 27, 2014

Check Out History Podcasts at Blog Talk Radio with 3600seconds on BlogTalkRadio with 3600seconds on BlogTalkRadio

For more on "Hubert Harrison: The Voice of Harlem Radicalism" Click Here and Click Here

Also see the video on Hubert Harrison Here

Read More

“Hubert Harrison: The Voice of Harlem Radicalism” Presentation by Jeffrey B. Perry

May 8, 2014

“Hubert Harrison: The Voice of Harlem Radicalism”

Presentation by Jeffrey B. Perry

Dudley Public Library, Roxbury, Massachusetts,

February 15, 2014

The event was hosted by Mimi Jones and sponsored by Friends of the Dudley Library, Alliance for a Secular and Democratic South Asia, and Massachusetts Global Action. Contact people included Mirna Lascano, Umang Kumar, and Charlie Welch in addition to Mimi.

Video Prepared by Boston Neighborhood News TV’s “Around Town” -- Channel: Comcast 9 / RCN 15 Justin D. Shannahan, Production Manager, Ted Lewis, cameraman, and Laura Kerivan, copy editor for Boston Neighborhood Network Television. Nia Grace, Marketing and Promotions Manager of BNNTV, and Scott Mercer, of BNNTV, coordinated efforts to make the video available.

For additional information on Hubert Harrison CLICK HERE

and CLICK HERE

Note: The presentation and Question and Answer period lasted over 2 hours. The TV station edited it down to this length. There was much more presentation and discussion. Also, the crowd was remarkable since the event was at the highpoint of the winter’s big snowstorm, the governor was telling people to stay off the roads, and the public library closed early (only leaving a door open to the auditorium where this event was held). Those who made it to and stayed through the event were determined and this was manifested in their interest during the presentation, the lengthy Q and A period (some of which was cut), and much informal discussion that went on into the evening.

For Boston Neighborhood News TV’s “Around Town” -- Channel: Comcast 9 / RCN 15 on the internet Click Here or Click Here

For more on Hubert H. Harrison and on the work of Theodore W. Allen see “The Developing Conjuncture and some Insights from Hubert Harrison and Theodore W. Allen on the Centrality of the Fight Against White Supremacy” available by >a href="www.jeffreybperry.net"> Clicking Here and going to top left

For those interested in a video on Theodore W. Allen’s work CLICK HERE

Read More

Hubert H. Harrison The Negro and the Nation 1917

March 21, 2014

The Negro and the Nation

(Cosmo-Advocate Publishing Company

2305 Seventh Avenue, New York

1917

In August 1917, shortly after founding the first organization (The Liberty League) and the first newspaper (The Voice) of the “New Negro Movement,” Hubert Harrison completed his first book -- The Negro and the Nation.

The book was published by the Cosmo-Advocate Publishing Company, which was headed by Barbados-born Orlando M. Thompson (a future Vice-President of the Black Star Line) and included Barbados-born Richard B. Moore (a Socialist and bibliophile and future Communist and Scottsboro Boys orator) as a part owner.

Harrison was at a highpoint in popularity and the book's "Introductory" described in detail how the World War had quickened the development of race consciousness. The book then reprinted some of Harrison's early articles -- "The Black Man's Burden" (1912), "Socialism and the Negro" (c. 1912), "The Real Negro Problem" (c. 1912), "On A Certain Conservatism in Negroes" (1914), "What Socialism Means To Us" (1912), and "The Negro and the Newspapers" (c. 1910-1912).

In the "Preface" Harrison explained that the reprinted articles helped to describe “the present situation of the Negro in present day America” and showed” how that situation re-acts upon the mind of the Negro." He emphasized that such exposure was the "Negro's" immediate "great need."

In the “Preface" he also indicated that he planned, in the near future, to write a book "on the New Negro" which would "set forth the aims and ideals” of the new movement “which has grown out of the international crusade 'for democracy -- for the right to have A VOICE in their own government' -- as President Wilson so sincerely put it."

In 1919 Harrison would edit The New Negro: A Monthly Magazine of a Different Sort -- “intended as an organ of the international consciousness of the darker races -- especially of the Negro race.”

Then, in 1920, Harrison did complete that second book -- When Africa Awakes: The “Inside Story” of the Stirrings and Strivings of the New Negro in the Western World (The Porro Press, 513 Lenox Ave, New York, August 1920). In the “Introductory” to that work Harrison writes: “It is hardly necessary to point out that the AFRICA of the title is to be taken in its racial rather than its geographical sense.”

To read The Negro and the Nation CLICK HERE

For additional information by and about Hubert Harrison CLICK HERE

Read More

Anselmo Jackson Discusses Hubert Harrison’s Influence on Marcus Garvey

September 10, 2013

Anselmo Jackson, a writer for both Hubert Harrison’s “Voice” and Marcus Garvey’s “Negro World,” writes that beginning in 1916,

“outdoors and indoors, Hubert Harrison was preaching an advanced type of radicalism with a view to impressing race consciousness and effecting racial solidarity among Negroes. The followers of Harrison, responding to his demand that a New Negro Manhood movement among Negroes be organized, formed the Liberty League fo[r] Negro-Americans, a short while prior to Garvey. . . . The . . . atmosphere was charged with Harrison’s propaganda; men and women of color thruout the United States and the West Indies donated their dollars and pledged their support to Harrison as they became members of the Liberty League.

Garvey publicly eulogized Harrison, joined the Liberty League and took a keen interest in its affairs. . . . Harrison rendered memorable educational and constructive community service to the Negroes of Harlem. It may be truly said that he was the forerunner of Garvey and contributed largely to the success of the latter by preparing the minds of Negroes through his lectures, thereby molding and developing a new temper among Negroes which undoubtedly made the task of the Jamaican much easier than it otherwise would have been.”

For more on Hubert Harrison: The Voice of Harlem Radicalism, 1883-1918 click here, here and here

Read More

“outdoors and indoors, Hubert Harrison was preaching an advanced type of radicalism with a view to impressing race consciousness and effecting racial solidarity among Negroes. The followers of Harrison, responding to his demand that a New Negro Manhood movement among Negroes be organized, formed the Liberty League fo[r] Negro-Americans, a short while prior to Garvey. . . . The . . . atmosphere was charged with Harrison’s propaganda; men and women of color thruout the United States and the West Indies donated their dollars and pledged their support to Harrison as they became members of the Liberty League.

Garvey publicly eulogized Harrison, joined the Liberty League and took a keen interest in its affairs. . . . Harrison rendered memorable educational and constructive community service to the Negroes of Harlem. It may be truly said that he was the forerunner of Garvey and contributed largely to the success of the latter by preparing the minds of Negroes through his lectures, thereby molding and developing a new temper among Negroes which undoubtedly made the task of the Jamaican much easier than it otherwise would have been.”

For more on Hubert Harrison: The Voice of Harlem Radicalism, 1883-1918 click here, here and here

Read More

HAPPY BIRTHDAY HUBERT H. HARRISON April 27, 1883 -- December 17, 1927

April 26, 2013

Hubert Harrison (1883-1927) is one of the truly important figures of early twentieth-century America. A brilliant writer, orator, educator, critic, and political activist, he was described by the historian Joel A. Rogers, in World’s Great Men of Color as “the foremost Afro-American intellect of his time.” Rogers adds that “No one worked more seriously and indefatigably to enlighten” others and “none of the Afro-American leaders of his time had a saner and more effective program.” Labor and civil rights leader A. Philip Randolph described Harrison as “the father of Harlem Radicalism.” Harrison’s friend and pallbearer, Arthur Schomburg, fully aware of his popularity, eulogized to the thousands attending Harrison’s Harlem funeral that he was also “ahead of his time.”

Born in St. Croix, Danish West Indies, in 1883, to a Bajan mother and a Crucian father, Harrison arrived in New York as a seventeen-year-old orphan in 1900. He made his mark in the United States by struggling against class and race oppression, by helping to create a remarkably rich and vibrant intellectual life among African Americans, and by working for the enlightened development of the lives of “the common people.” He consistently emphasized the need for working class people to develop class consciousness; for “Negroes” to develop race consciousness, self-reliance, and self-respect; and for all those he reached to challenge white supremacy and develop modern, scientific, critical, and independent thought as a means toward liberation.

A self-described “radical internationalist,” Harrison was extremely well-versed in history and events in Africa, Asia, the Mideast, the Americas, and Europe. More than any other political leader of his era, he combined class consciousness and anti-white supremacist race consciousness in a coherent political radicalism. He opposed capitalism and maintained that white supremacy was central to capitalist rule in the United States. He emphasized that “politically, the Negro is the touchstone of the modern democratic idea”; that “as long as the Color Line exists, all the perfumed protestations of Democracy on the part of the white race” were “downright lying”; that “the cant of ‘Democracy’” was “intended as dust in the eyes of white voters”; and that true democracy and equality for “Negroes” implied “a revolution . . . startling even to think of.”

Working from this theoretical framework, he was active with a wide variety of movements and organizations and played signal roles in the development of what were, up to that time, the largest class radical movement (socialism) and the largest race radical movement (the “New Negro”/Garvey movement) in U.S. history. His ideas on the centrality of the struggle against white supremacy anticipated the profound transformative power of the Civil Rights/Black Liberation struggles of the 1960s and his thoughts on “democracy in America” offer penetrating insights on the limitations and potential of America in the twenty-first century.

Harrison served as the foremost Black organizer, agitator, and theoretician in the Socialist Party of New York during its 1912 heyday; he founded the first organization (the Liberty League) and the first newspaper (The Voice) of the militant, World War I-era “New Negro” movement; and he served as the editor of the Negro World and principal radical influence on the Garvey movement during its radical high point in 1920. His views on race and class profoundly influenced a generation of “New Negro” militants including the class radical A. Philip Randolph and the race radical Marcus Garvey.

Considered more race conscious than Randolph and more class conscious than Garvey, Harrison is the key link in the ideological unity of the two great trends of the Black Liberation Movement--the labor and civil rights trend associated with Martin Luther King, Jr., and the race and nationalist trend associated with Malcolm X. (Randolph and Garvey were, respectively, the direct links to King marching on Washington, with Randolph at his side, and to Malcolm, whose parents were involved with the Garvey movement, speaking militantly and proudly on street corners in Harlem.)

Harrison was not only a political radical, however. Rogers described him as an “Intellectual Giant and Free-Lance Educator,” whose contributions were wide-ranging, innovative, and influential. He was an immensely skilled and popular orator and educator who spoke and/or read six languages; a highly praised journalist, critic, and book reviewer (reportedly the first regular Black book reviewer "in Negro newspaperdom"); a pioneer Black activist in the freethought and birth control movements; a bibliophile and library builder and popularizer who helped develop the 135th Street Public Library into what became known as the internationally famous Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture; a pioneer Black lecturer for the New York City Board of Education, and one of its foremost orators). His biography offers profound insights on race, class, religion, immigration, war, democracy, and social change in America.

For reviewers' comments from scholars and activists on “Hubert Harrison: The Voice of Harlem Radicalism, 1883-1918” CLICK HERE and CLICK HERE.

For Columbia University Press’s page on the biography CLICK HERE

For a link to some writings by and about Hubert Harrison CLICK HERE

“Hubert Harrison: The Voice of Harlem Radicalism, 1883-1918” (the first volume of a projected two-volume biography of Harrison) is now on sale at a special 50% off discount.

It is selling for $14 in paperback from Columbia University Press through April 30, 2013 CLICK HERE

(To save 50% simply use the coupon code "SALE" in your shopping cart after you have entered the book for your order, click "apply" and your savings will be calculated.)

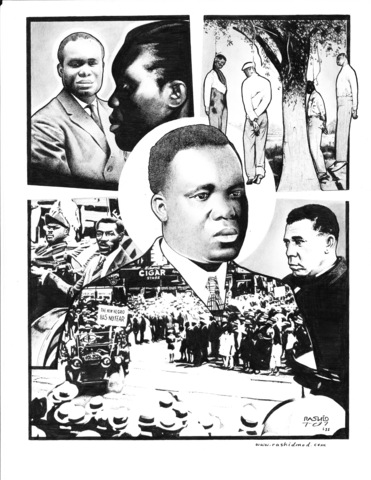

Artist Kevin “Rashid” Johnson is Defense Minister of the New Afrikan Black Panther Party – Prison Chapter (not to be confused with the “New Black Panther Party”). He is the author of Defying the Tomb: Selected Prison Writings and Art, Featuring Exchanges with an Outlaw (2010), "Political Struggle in the Teeth of Prison Reaction: From Virginia to Oregon,", Socialism and Democracy, Vol. 27, No. 1 (2013), 78-94, other articles in Socialism & Democracy (nos. 38 and 43), and many other works available online. Address: Kevin Johnson, no. 19370490, Snake River Correctional Institution, 777 Stanton Blvd., Ontario, OR 97914.

Read More

"The Letter to the Editor that 'Science and Society' Refused to Publish"

February 5, 2012

To: David Laibman, Editor of "Science and Society"

From: Jeffrey B. Perry, jeffreybperry@gmail.com, www.jeffreybperry.net

Correspondence Submission

Re: Review of "Hubert Harrison: The Voice of Harlem Radicalism, 1883-1918" (in April 2011 issue)

August 5, 2011

“In the first place, remember that in a book review you are writing for a public who want to know whether it is worth their while to read the book about which you are writing. They are primarily interested more in what the author set himself to do and how he does it than in your own private loves and hates.”

Hubert Harrison, 1922

St. Croix-born, Harlem-based Hubert Harrison (1883-1927) was described by the historian Joel A. Rogers in "World’s Great Men of Color" as “the foremost Afro-American intellect of his time.” A. Philip Randolph referred to him as the “Father of Harlem Radicalism.” (Perry, 2008, 1, 5)

Harrison merited such praise. He was a radical political activist who served as the foremost Black organizer, agitator, and theoretician in the Socialist Party of New York during its 1912 heyday; as the founder and leading figure of the militant, World War I-era “New Negro” movement; and as the editor of the "Negro World" and principal radical influence on the Garvey movement during its radical high point in 1920. He was also a class conscious and race conscious “radical internationalist” whose views profoundly influenced a generation of “New Negro” militants that included the class-radical socialists Randolph and Chandler Owen, the future communists Cyril V. Briggs, Richard B. Moore, and Williana Burroughs, and the race radical Marcus Garvey. Considered more race conscious than Randolph and Owen and more class conscious than Garvey, Harrison is a seminal figure in 20th century Black radicalism. (Perry, 2008, 2, 4, 94, and 437-38 n. 45)

He was not only a political radical, however. Harrison was also an immensely popular orator and freelance educator; a highly praised journalist, editor, and book reviewer; a promoter of Black writers and artists; a pioneer Black activist in the freethought and birth control movements; and a bibliophile and library popularizer (who helped develop the 135th Street Public Library into an international center for research in Black culture). In his later years he was the leading Black lecturer for the New York City Board of Education. (Perry, 2008, 5-6)

One area where Harrison, has much to offer, concerns book reviewing. At age twenty-four he authored two front-page "New York Times Saturday Review of Books" pieces on literary criticism; he initiated what was described as the “first regular book review section known to Negro newspapedom”; he authored some 70 reviews and regularly reviewed books in the newspapers that he edited including "The Voice" (1917-1918), "New Negro" (1919), and "Negro World" (1920); he was praised for his insights as a critic by Nobel Prize winner Eugene O’Neill; and he has recently been described as a “patron saint” of book reviewers by Scott McLemee in the online "Columbia Journalism Review." It was in the "Negro World" that Harrison offered the sound advice on book reviewing quoted in the epigraph above. (Perry, 2001, 2, 295-6)

I think "Science and Society" readers would have been better served if Margaret Stevens, in her April 2011 review of "Hubert Harrison: The Voice of Harlem Radicalism, 1883-1918," had followed Harrison’s advice more closely and if she had put more accuracy and less innuendo (Harrison’s “predilection,” “it is curious,” “it is curious that Perry, repeatedly,” etc.) in her review. Readers would have been better informed about both Harrison and the biography and they would be better able to decide, in Harrison’s words, “whether it is worth their while to read the book.”

Here are some failings of the review –

1. Stevens writes that “Perry . . . emphasizes Harrison’s role in founding the Liberty League in Harlem . . . . He does not, however, examine Harrison’s continuing ties with ‘old crowd’ Black leaders such as Booker T. Washington and W. E. B. Du Bois.”

Regarding Washington, Stevens’ statement makes absolutely no sense. Harrison was an outspoken critic of Washington for years, described him as a “subservient,” and characterized his political philosophy as “one of submission and acquiescence in political servitude.” Harrison was summarily fired from the Post Office through the efforts of Washington’s “Tuskegee Machine” (in 1911) after writing two letters to the "New York Sun" critical of Washington. Stevens’ statement also makes no sense since Washington died in 1915 – over a year-and-a-half before the founding of Harrison’s Liberty League in June 1917! (Perry, 2008, 123, 132-3, 261, 285, 389)

Regarding Du Bois, in Hubert Harrison I describe how Harrison started out as a supporter of Du Bois and how political differences emerged in the period covered by the first volume.

Harrison differed from Du Bois on “The Talented Tenth,” which Du Bois described as the “educated and gifted” group whose members “must be made leaders of thought and missionaries of culture among their people.” Harrison thought that the “Talented Tenth” hadn’t provided the leadership that was needed, that they should come down from their Mt. Sinais and get among the people, and that the “Colored” leadership implicit in that concept was not “pre-ordained” to lead Black people.(Perry, 2008, 125, 238)

During 1911-12 Harrison, drawing from the work of autonomous women’s clubs and Foreign Language Federations in the SP, initiated a Colored Socialist Club in a special effort to attract “Negroes” to the party. Du Bois, while still an SP member, did not support that effort. (Perry, 2008, 148, 169-71)

In the 1912 election Harrison supported and campaigned vigorously for the SP Presidential candidate Eugene V. Debs, while Du Bois left the SP in order to support Woodrow Wilson, the Democratic Party candidate. (Perry, 2008, 19, 269, 281)

In 1916 Harrison articulated a plan for developing bottom-up race unity that would eventually lead to the founding of the Liberty League. The plan was consciously in opposition to the approaches of both Washington and Du Bois whom Harrison felt started at the wrong end – i.e. they began at the top when they should have began at the bottom. Interestingly, in his third autobiography, "Dusk of Dawn" (1940), Du Bois would reach a similar conclusion. (Perry, 2008, 271)

In 1917-1918 with the Liberty League and then with the Liberty Congress Harrison advocated federal anti-lynching legislation, which the NAACP declined to push at this time and did not publicly support until later. In 1917, according to historian Robert L. Zangrando in "The NAACP Crusade Against Lynching, 1909-1950," the NAACP “actually declined to make an open push for” federal anti-lynching legislation.” Zangrando concluded that NAACP’s failure to wholeheartedly support the anti-lynching legislation reflected the fact that it “was reaching for southern support and still pulling its punches on the matter of federal statute.” (Perry, 2008, 9, 288-9, 298-9, 310, 375, 381, 515 n 29)

The Harrison/William Monroe Trotter-led Liberty Congress of 1918 was a major Black national protest effort during World War I. It opposed lynching, segregation, and disfranchisement and petitioned Congress for federal anti-lynching legislation. Joel E. Spingarn, the head of the NAACP, attempted to have it called off. Spingarn was a major in Military Intelligence (that branch of the War Department that monitored the Black and radical communities) and he was a pro-war socialist at a time when Lenin and others in the international socialist movement were criticizing that position. When Spingarn’s attempt to get the Liberty Congress called-off didn’t work, he spoke with Du Bois and they agreed to host a “Colored Editors Conference” to meet a week earlier in a blatant effort to steal the thunder from, and undermine, the Liberty Congress. In this period Du Bois put in an application for a captaincy in Military Intelligence and, as part of the quid-pro-quo related to his captaincy application, he wrote his infamous July 1918 "Crisis" editorial entitled “Close Ranks.” In that editorial Du Bois urged African Americans to “forget our special grievances [lynching, segregation, disfranchisement] and close ranks” behind Wilson’s war effort. (Perry, 2008, 232, 373-6, 381, 385-6, 473-4 n 36)

In response to Du Bois’s “Close Ranks” editorial and his application for the captaincy in Military Intelligence, Harrison wrote a scathing editorial in "The Voice" entitled “The Descent of Dr. Du Bois.” Harrison’s exposé was a principal reason that Du Bois was denied the captaincy and, more than any other document, it marked the significant break between the “New Negroes” and the older leadership. (Perry, 2008, 386-91, 408 n. 34; Aptheker, 1983, 159)

Because of such criticism, Du Bois never mentioned Harrison in "The Crisis" and seemingly went out of his way to avoid doing so. (Perry, 2008, 352-3, 386-91, 408 n 34.)

2. Stevens questions my “placing Harrison rather than Garvey at the helm of Harlem’s burgeoning Black radical community” and not “more clearly” elucidating some related “larger theoretical and historical” issues (which she does not name or define).

The record left by contemporaries is clear about Harrison's importance as a radical and his signal influence on Garvey's radicalism. Through mid-1918 (when volume one ends) Harrison was clearly the dominant figure in Harlem radicalism. For anyone to even suggest that Garvey, not Harrison was the dominant radical figure at that time, is, based on the record, utter nonsense. My biography sought to document what actually happened and I think this is a proper task for both a biographer and an historian.