Jeffrey B. Perry Blog

Facts of the current conjuncture . . .millions are suffering under the white supremacist shaping of this system, . . . .

August 25, 2015

As the economic situation worsens people are encouraged to read “The Developing Conjuncture and Some Insights From Hubert Harrison and Theodore W. Allen on the Centrality of the Fight Against White Supremacy” at the TOP LEFT HERE or at Cultural Logic HERE

Harrison and Allen were two of the twentieth century’s most important thinkers on issues of race and class and they have much to offer for struggles ahead.

“Overall, the facts of the current conjuncture indicate that millions of poor and working people are suffering under U.S. capitalism, that millions are suffering under the white supremacist shaping of this system, that these conditions are inter-related, and that these conditions are worsening.”

Table of Contents

Epigraph

Introduction

Hubert Harrison

Theodore W. Allen

Harrison and Allen and the Centrality of the Struggle Against White-Supremacy

Some Class and Racial Aspects of The Conjuncture

Deepening Economic Crisis

U.S. Workers Faring Badly

White Supremacist Shaping

Wisconsin

Millions are Suffering and Conditions are Worsening

Insights from Hubert Harrison

Arrival in America, Contrast with St. Croix

Socialist Party Writings

“Southernism or Socialism – which?”

The Socialist Party Puts [the “White”] Race First and Class After

Class Consciousness, White Supremacy, and the "Duty to Champion the Cause of the Negro"

On “The Touchstone” and the Two-Fold Character of Democracy in America

Concentrated Race-Conscious Work in the Black Community

Capitalist Imperialism and the Need to Break Down Exclusion Walls of White Workers

The International Colored Unity League

Struggle Against White Supremacy is Central

Insights from Theodore W. Allen

Early Research and Writings and Pioneering Use of “White Skin Privilege” Concept

White Blindspot

Why No Socialism? . . . and The Main Retardant to Working Class Consciousness

The Role of White Supremacy in Three Previous Crises

The Great Depression . . . and the White Supremacist Response

Response to Four Arguments Against and Five “Artful Dodges”

Early 1970s Writings and Strategy

“The Invention of the White Race”

Other Important Contributions in Writings on the Colonial Period

Inventing the “White Race” and Fixing “a perpetual Brand upon Free Negros”

Political Economic Aspects of the Invention of the “White Race”

Racial Oppression and National Oppression

“Racial Slavery” and “Slavery”

Male Supremacy, Gender Oppression, and Laws Affecting the Family

Slavery as Capitalism, Slaveholders as Capitalists, Enslaved as Proletarians

Class-Conscious, Anti-White Supremacist Counter Narrative – Comments on Jordan and Morgan

Not Simply a Social Construct, But a Ruling Class Social Control Formation . . . and Comments on Roediger

The “White Race” and “White Race” Privilege

On the Bifurcation of “Labor History” and “Black History” and on the “National Question”

Later Writings . . . “Toward a Revolution in Labor History”

Strategy

The Struggle Ahead

Addendum [re “Daedalus”]

Read More

Harrison and Allen were two of the twentieth century’s most important thinkers on issues of race and class and they have much to offer for struggles ahead.

“Overall, the facts of the current conjuncture indicate that millions of poor and working people are suffering under U.S. capitalism, that millions are suffering under the white supremacist shaping of this system, that these conditions are inter-related, and that these conditions are worsening.”

Table of Contents

Epigraph

Introduction

Hubert Harrison

Theodore W. Allen

Harrison and Allen and the Centrality of the Struggle Against White-Supremacy

Some Class and Racial Aspects of The Conjuncture

Deepening Economic Crisis

U.S. Workers Faring Badly

White Supremacist Shaping

Wisconsin

Millions are Suffering and Conditions are Worsening

Insights from Hubert Harrison

Arrival in America, Contrast with St. Croix

Socialist Party Writings

“Southernism or Socialism – which?”

The Socialist Party Puts [the “White”] Race First and Class After

Class Consciousness, White Supremacy, and the "Duty to Champion the Cause of the Negro"

On “The Touchstone” and the Two-Fold Character of Democracy in America

Concentrated Race-Conscious Work in the Black Community

Capitalist Imperialism and the Need to Break Down Exclusion Walls of White Workers

The International Colored Unity League

Struggle Against White Supremacy is Central

Insights from Theodore W. Allen

Early Research and Writings and Pioneering Use of “White Skin Privilege” Concept

White Blindspot

Why No Socialism? . . . and The Main Retardant to Working Class Consciousness

The Role of White Supremacy in Three Previous Crises

The Great Depression . . . and the White Supremacist Response

Response to Four Arguments Against and Five “Artful Dodges”

Early 1970s Writings and Strategy

“The Invention of the White Race”

Other Important Contributions in Writings on the Colonial Period

Inventing the “White Race” and Fixing “a perpetual Brand upon Free Negros”

Political Economic Aspects of the Invention of the “White Race”

Racial Oppression and National Oppression

“Racial Slavery” and “Slavery”

Male Supremacy, Gender Oppression, and Laws Affecting the Family

Slavery as Capitalism, Slaveholders as Capitalists, Enslaved as Proletarians

Class-Conscious, Anti-White Supremacist Counter Narrative – Comments on Jordan and Morgan

Not Simply a Social Construct, But a Ruling Class Social Control Formation . . . and Comments on Roediger

The “White Race” and “White Race” Privilege

On the Bifurcation of “Labor History” and “Black History” and on the “National Question”

Later Writings . . . “Toward a Revolution in Labor History”

Strategy

The Struggle Ahead

Addendum [re “Daedalus”]

Read More

Contents "The Developing Conjuncture and Some Insights From Hubert Harrison and Theodore W. Allen On the Centrality of the Fight Against White Supremacy" by Jeffrey B. Perry

August 2, 2015

Epigraph

Introduction

Hubert Harrison

Theodore W. Allen

Harrison and Allen and the Centrality of the Struggle Against White-Supremacy

Some Class and Racial Aspects of The Conjuncture

Deepening Economic Crisis

U.S. Workers Faring Badly

White Supremacist Shaping

Wisconsin

Millions are Suffering and Conditions are Worsening

Insights from Hubert Harrison

Arrival in America, Contrast with St. Croix

Socialist Party Writings

“Southernism or Socialism – which?”

The Socialist Party Puts [the “White”] Race First and Class After

Class Consciousness, White Supremacy, and the "Duty to Champion the Cause of the Negro"

On “The Touchstone” and the Two-Fold Character of Democracy in America

Concentrated Race-Conscious Work in the Black Community

Capitalist Imperialism and the Need to Break Down Exclusion Walls of White Workers

The International Colored Unity League

Struggle Against White Supremacy is Central

Insights from Theodore W. Allen

Early Research and Writings and Pioneering Use of “White Skin Privilege” Concept

White Blindspot

Why No Socialism? . . . and The Main Retardant to Working Class Consciousness

The Role of White Supremacy in Three Previous Crises

The Great Depression . . . and the White Supremacist Response

Response to Four Arguments Against and Five “Artful Dodges”

Early 1970s Writings and Strategy

“The Invention of the White Race”

Other Important Contributions in Writings on the Colonial Period

Inventing the “White Race” and Fixing “a perpetual Brand upon Free Negros”

Political Economic Aspects of the Invention of the “White Race”

Racial Oppression and National Oppression

“Racial Slavery” and “Slavery”

Male Supremacy, Gender Oppression, and Laws Affecting the Family

Slavery as Capitalism, Slaveholders as Capitalists, Enslaved as Proletarians

Class-Conscious, Anti-White Supremacist Counter Narrative – Comments on Jordan and Morgan

Not Simply a Social Construct, But a Ruling Class Social Control Formation . . . and Comments on Roediger

The “White Race” and “White Race” Privilege

On the Bifurcation of “Labor History” and “Black History” and on the “National Question”

Later Writings . . . “Toward a Revolution in Labor History”

Strategy

The Struggle Ahead

Addendum [re “Daedalus”]

To read the article CLICK HERE and go to top left,

or CLICK HERE.

To read the article without downloading a PDF CLICK HERE!

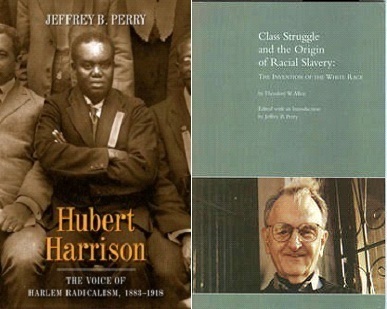

For information on “Hubert Harrison: The Voice of Harlem Radicalism, 1883-1918” (Columbia University Press) CLICK HERE

For writings by and about Hubert Harrison CLICK HERE

For a video presentation on Hubert Harrison, "The Father of Harlem Radicalism," who is discussed at the beginning of this video CLICK HERE

For information on Theodore W. Allen's "The Invention of the White Race" (Verso Books) CLICK HERE

For additional writings by and about Theodore W. Allen CLICK HERE

For a video presentation on Theodore W. Allen's "The Invention of the White Race," which draws insights from the life and work of Hubert Harrison CLICK HERE

For key insights from Theodore W. Allen on U.S. Labor History CLICK HERE

Read More

Jeffrey B. Perry Open Letter in Response to “Challenging White Privilege From the Inside” by Kyle Spencer in the "New York Times," February 20, 2015

February 22, 2015

Unfortunately, the “New York Times” article on “Challenging White Privilege From the Inside” (February 20, 2015) totally ignores the seminal contributions of Theodore W. Allen (1919-2005) who did pioneering work on “white privilege” and “white skin privilege” from the mid-1960s until his death in 2005.

Also ignored is the fact that by June 15, 1969, Allen’s work, and that of others, had impacted Students for a Democratic Society so much that the organization’s national office was calling "for an all-out fight against 'white skin privileges.'” (Thomas R. Brooks, "The New Left is Showing Its Age," “New York Times,” June 15, 1969, p. 20.)

Allen’s important analysis of “white privilege,” which was developed into his two-volume “classic” “The Invention of the White Race,” should be of interest to “Times” readers.

After pointing out that the word “white” as a symbol of social status did not appear in any Virginia Colonial Records until 1691 and demonstrating that the “white race,” as we know it, did not exist in early 17th Century Virginia (the pattern-setting plantation colony), Allen develops the thesis that the “white race” was invented as a ruling class social control formation in response to labor solidarity as manifested in the later, civil war stages of Bacon's Rebellion (1676-77).

To this he adds two important corollaries: 1) the ruling elite, in its own class interest, deliberately instituted a system of “white race” privileges to define and maintain the “white race” and to establish a system of racial oppression; and 2) the consequences were not only ruinous to the interests of African-Americans, they were also “disastrous” for European-American workers, whose class interests differed fundamentally from those of the ruling elite. He describes these “white privileges” as a “poison bait” (like a shot of heroin) for European-American workers.

Allen’s work also challenges “The Great White Assumption” – “the unquestioning, indeed unthinking acceptance of the ‘white’ identity of European-Americans of all classes as a natural attribute rather than a social construct.”

In addition, Allen shied away from the term “whiteness.” As he explained, “it’s an abstract noun, it’s an abstraction, it’s an attribute of some people, it’s not the role they play. And the white race is an actual objective thing. It’s not anthropologic, it’s a historically developed identity of European Americans and Anglo-Americans and so it has to be dealt with. It functions . . . in this history of ours and it has to be recognized as such . . . to slough it off under the heading of ‘whiteness,’ to me seems to get away from the basic white race identity problem.”

Theodore W. Allen’s work is essential for understanding “white privilege” and the “white race.”

The fullest treatment of the development of Theodore W. Allen’s work can be found in “The Developing Conjuncture and Some Insights From Hubert Harrison and Theodore W. Allen on the Centrality of the Fight Against White Supremacy,” available in PDF format HERE (at the top left) and HERE.

For information on Theodore W. Allen’s Vol. II: "The Origin of Racial Oppression in Anglo America" (including comments from scholars and activists) published by Verso Books with a new, internal study guide CLICK HERE.

For information on Theodore W. Allen’s Vol. I: “Racial Oppression and Social Control" (including comments from scholars and activists) published by Verso Books with a new, internal study-guide CLICK HERE.

For articles, audios, and videos by and about Theodore W. Allen CLICK HERE.

For Sean Ahern’s review of Theodore W. Allen’s “The Invention of the White Race” (Verso Books) in "Black Commentator" CLICK HERE.

For another video “On Theodore W. Allen, ‘The Invention of the White Race,’ and White Supremacy in U.S. Labor History” – An Interview with Jeffrey B. Perry at the Labor and Working Class History Association Conference in New York City CLICK HERE.

Read More

"In Memoriam: Theodore William Allen (1919-2005)" by Jeffrey B. Perry (re-posted after the fourth anniversary of his death)

February 25, 2009

Theodore W. Allen, a working class intellectual and activist and author of the influential two-volume history The Invention of the White Race (Verso:1994, 1997), died on January 19, 2005, surrounded by friends in his apartment at 97 Brooklyn Avenue in the Crown Heights section of Brooklyn. He was 85. The cause of death was cancer, which he had battled for 15 years. Announcement of the death was made by his close friend Linda Vidinha.

Allen, an ardent opponent of white supremacy, spent much of his last forty years researching the role of white supremacy in United States history and examining records of colonial Virginia as he documented and analyzed the development of the "white race" in the latter part of the seventeenth century. His main thesis, that the "white race" developed as a ruling class social control formation in response to labor unrest as manifest in Bacon's Rebellion of 1676-77, was first articulated in February 1974 in a talk he delivered at a Union of Radical Political Economists meeting in New Haven. Versions of that talk were published in 1975 in Radical America

In the 1960s "Ted" Allen significantly influenced the direction of the student movement and the new left with an article entitled "Can White Radicals Be Radicalized?" which developed the argument that white supremacy, reinforced among European Americans by the "white skin privilege," was the main retardant of working class consciousness in the United States and that efforts at radical social change should direct principal efforts at challenging the system of white supremacy and urging "repudiation of white skin privilege" by European Americans.

Allen was in the forefront in challenging phenotypical (physical appearance-based) definitions of race, in challenging "racism is innate" arguments, in challenging theories that the working class benefits from white supremacy, in calling attention to the crucial role of the buffer social control group in racial oppression, in documenting and analyzing the development of the "white race" in the latter part of the seventeenth century, and in clarifying how "this all-class association of European-Americans held together by 'racial' privileges conferred on laboring class European-Americans relative to African-Americans--[has served] as the principal historic guarantor of ruling-class domination of national life" in the United States. These contributions differentiate his work from many writers in the rapidly growing white race as "a social and cultural construction" ranks, which his writings helped to spawn.

In The Invention of the White Race Allen focused on Virginia, the first and pattern-setting continental colony. He emphasized that "When the first Africans arrived in Virginia in 1619, there were no white people there" and he added that he found "no instance of the official use of the word 'white' as a token of social status before its appearance in a Virginia law passed in 1691." He also found, similar to historian Lerone Bennett, Jr., that throughout most of the seventeenth century conditions for African-American and European-American laborers and bond-servants were very similar. Under such conditions solidarity among the laboring classes reached a peak during Bacon's Rebellion: the capitol (Jamestown) was burned; two thousand rebels forced the governor to flee across the Chesapeake Bay and controlled 6/7 of Virginia's land; and, in the latter stages of the struggle, "foure hundred English and Negroes in Arms" demanded their freedom from bondage.

To Allen, the social control problems highlighted by Bacon's Rebellion "demonstrated beyond question the lack of a sufficient intermediate stratum to stand between the ruling plantation elite and the mass of European-American and African-American laboring people, free and bond." He then detailed how, in the period after Bacon's Rebellion the white race was invented as "a bourgeois social control formation in response to [such] laboring class unrest." He described systematic ruling class policies, which extended privileges to European laborers and bond-servants and imposed and extended harsher disabilities and blocked normal class mobility for African-Americans. Thus, for example, when African-Americans were deprived of their long-held right to vote in Virginia and Governor William Gooch explained in 1735 that the Virginia Assembly had decided upon this curtailment of the franchise in order "to fix a perpetual Brand upon Free Negros & Mulattos," Allen emphasized that this was not an "unthinking decision"! "Rather, it was a deliberate act by the plantation bourgeoisie; it proceeded from a conscious decision in the process of establishing a system of racial oppression, even though it meant repealing an electoral principle that had existed in Virginia for more than a century."

For Allen, "The hallmark, the informing principle, of racial oppression in its colonial origins and as it has persisted in subsequent historical contexts, is the reduction of all members of the oppressed group to one undifferentiated social status, beneath that of any member of the oppressor group." The key to understanding racial oppression, he wrote, is the social control buffer -- that group in society, which helps to control the poor for the rich. Under racial oppression in Virginia, any persons of discernible non-European ancestry in colonial Virginia after Bacon's Rebellion were denied a role in the social control buffer group, the bulk of which was made up of working-class "whites." In contrast, Allen explained, in the Caribbean "Mulattos" were included in the social control group and were promoted into middle-class status. For him, this was "the key to the understanding the difference between Virginia ruling-class policy of 'fixing a perpetual brand' on African-Americans" and "the policy of the West Indian planters of formally recognizing the middle-class status 'colored' descendant (and other Afro-Caribbeans who earned special merit by their service to the regime)." The difference "was rooted in the objective fact that in the West Indies there were too few laboring-class Europeans to embody an adequate petit bourgeoisie, while in the continental colonies there were too many to be accommodated in the ranks of that class." (In 1676 in Virginia, for example, there were approximately 6,000 European-American bond-laborers and 2,000 African-American bond-laborers.)

In 1996, on radio station WBAI in New York, Allen discussed the subject of "American Exceptionalism" and the much-vaunted "immunity" of the United States to proletarian class-consciousness and its effects. His explanation for the relatively low level of class consciousness was that social control in the United States was guaranteed, not primarily by the class privileges of a petit bourgeoisie, but by the white-skin privileges of laboring class whites; that the ruling class co-opts European-American workers into the buffer social control system against the interests of the working class to which they belong; and that the "white race" by its all-class form, conceals the operation of the ruling class social control system by providing it with a majoritarian "democratic" facade.

Theodore William Allen, the third child (after a sister Eula May and brother Tom) of Thomas E. and Almeda Earl Allen was born into a middle-class family August 23, 1919, in Indianapolis, Indiana. His father was a sales manager and his mother a housewife. In 1929 the family moved to Huntington, West Virginia, where, Ted was, in his words, "proletarianized by the Great Depression." He attended college for a couple of days after high school, but, because he didn't believe that setting encouraged independent thought, he didn't think it was for him and didn't go back.

At age 17 he joined the American Federation of Musicians (Local 362) and served as its delegate to the Huntington Central Labor Union, AFL. He continued work in the trade union movement as a coal miner in West Virginia for three years until he was forced to leave because of a back injury. During that period he belonged to United Mine Worker locals 5426 (Prenter, West Virginia), 6206 (Gary, West Virginia) where he was an organizer and Local President, and 4346 (Barrackville, West Virginia). He also was co-organizer of a trade union organizing program for the Marion County West Virginia Industrial Union Council, CIO.

In 1938 Allen married Ruth Voithofer, one of eleven children in a coal-mining family, whom he first met in 1934. Ruth was active in organizing and educational work among mining families and women and, beginning in 1942, was a prominent organizer for the United Electrical Workers Union. They separated in the mid-1940s and Ruth Newell (her name after re-marrying) died in 1999.

In 1948 Ted moved to New York. He had joined the Communist Party in the 1930s and, after coming to New York, he taught classes in economics at the Party's Jefferson School at Union Square in Manhattan (1949-56). He was also active in community, civil rights, trade union, and student organizing work; he worked in a factory, as a retail clerk, as a mechanical design draftsman, as an elevator operator, and as a junior high school math teacher at the Grace Church School in Greenwich Village.

In the 1950s Ted married Marie Strong, a poet, and became stepfather to her son, Michael. In the late 1950s the Communist Party went through major repression and internal struggle and Ted left the Party in order to help establish a new organization the Provisional Organizing Committee to Reconstitute the Communist Party (POC). In this period he wrote a number of economic and political articles on the economic situation in the United States and he argued that neither United States nor Latin American workers benefited from imperialism. In 1962 Marie died tragically and Ted, suffering greatly from her loss, discontinued work with the POC and traveled to England and Ireland.

By the mid 1960s, back in Brooklyn, and increasingly affected by the political climate marked by the growing civil rights movement, struggles for national liberation and socialism, and the Vietnam War, Allen set about taking a fresh look at the world and at his former beliefs. Nothing would be sacred. Though his formal education had ended with high school, he was a trained economist, he read widely in history, politics, literature, and the sciences, and he had a probing and analytical mind -- all of which would serve him well in the work ahead.

Drawing on the insights of W. E .B. Du Bois in Black Reconstruction on the blindspot of America, which he paraphrased as "the white blindspot," Allen began work on a historical study of three crises in United States history in which there were general confrontations of the forces of capital and those from below -- the crises of The Civil War and Reconstruction, the Populist Revolt of the 1890s, and the Great Depression of the 1930s. His work focused on the role of the theory and practice of white supremacy in shaping those outcomes. He worked together with his friend, the late Esther Kusic, and his work influenced another friend, Noel Ignatin [Ignatiev]. Together, Ignatin and Allen provided the copy for an influential pamphlet containing both "White Blindspot," under Ignatin's name, and Allen's article "Can White Radicals Be Radicalized."

Allen argued against what he referred to as the current consensus on U.S. labor history -- one which attributed the low level of class consciousness among American workers to such factors as the early development of civil liberties, the heterogeneity of the work force, the "safety valve" of homesteading opportunities in the West, the ease of social mobility, the relative shortage of labor, and the early development of "pure and simple trade unionism." He emphasized that each of these rationales had to be reinterpreted in terms of white supremacy, that white supremacy was reinforced by the white-skin privilege of white workers, and "that the white-skin privilege does not serve the real interests of the white workers."

The pamphlet, which issued a call to action -- "to repudiate the white-skin privilege" -- was published by the SDS-affiliated Radical Education Project and it had immediate effect on the left. It sharply posed the issues of how to fight white supremacy and whether, or not, that fight was in the interest of "white" workers. It also set the terms of discussion and debate for many activists within SDS.

Allen developed the analysis in his article into a still unpublished book-length manuscript entitled "The Kernel and the Meaning" (1972). It was then, in 1972, in the course of this work, that he became convinced that the problems related to white supremacy couldn't be resolved without a history of the plantation colonies of the 17th and 18th century. His reasoning was clear -- white supremacy still ruled in the United States more than a century after the abolition of slavery and the reasons for that had to be explained. He proceeded to search for a structural principle that was essential to the social order based on slave labor in the continental plantation colonies and still was essential to late twentieth-century America's social order based on wage-labor.

Over the next twenty years Allen did extensive primary research in colonial Virginia records (and his unpublished transcripts of this work, with his eye for the conditions of labor, are another of his important historical contributions). In this period he generated other unpublished book-length manuscripts including "The Genesis of the Chattel-Labor System in Continental Anglo-America" and "The Peculiar Seed," both of which dealt with the early 17th-century development of chattel bond-servitude in Virginia, under which workers could be bought and sold like property. (This chattelization of labor was done primarily among European American workers at first.)

When the first volume of The Invention of the White Race appeared it drew on, and challenged, the work of some of America's leading colonial historians including Winthrop Jordan and Edmund S. Morgan. It offered important theoretical and historical insights in the struggle against white supremacy when it challenged the two major arguments which tend to undermine the struggle against white supremacy in the working class -- the notion that racism is innate (as suggested by Jordan's "unthinking decision" explanation) and the notion that European-American workers benefit from racism (as suggested by Morgan's "there were too few free poor on hand to matter").

Allen challenged these ideas with his factual presentation and analysis, by providing a comprehensive alternate explanation, and by skillfully drawing on examples from Ireland (where a religio/racial oppression existed under the Protestant Ascendancy) and the Caribbean (where a different social control formation was developed based on promotion of "Mulattos" to petit-bourgeois status). He concluded that the codifications of the Penal Laws of the Protestant Ascendancy in Ireland and the slave codes of white supremacy in continental Anglo-America presented four common defining characteristics of those two regimes: 1) declassing legislation, directed at property-holding members of the oppressed group; 2) the deprivation of civil rights; 3) the illegalization of literacy; and 4) displacement of family rights and authorities. This understanding of racial oppression led him to conclude that a comparative study of "Protestant Ascendancy" in Ireland, and "white supremacy" in continental Anglo-America (in both its colonial and regenerate United States forms) demonstrates that racial oppression is not dependent upon differences of "phenotype."

While working on The Invention of the White Race Allen taught as an adjunct history instructor at Essex County Community College in Newark, NJ, and worked several years each on the staff of the Brooklyn Museum, as a postal mail handler in Jersey City, NJ, and as a librarian at the Brooklyn Public Library. Constantly at the edge of poverty his scholarship was remarkable for its dedication and tenacity in the face of great personal difficulties. During this period his research in Virginia was facilitated by the generosity of Ed Peeples and his family in Richmond and his work in Brooklyn was encouraged by his former companion and close friend Linda Vidinha, her family and her companion Marsha Rosenthal, and a number of other close friends and neighbors who supported his efforts in numerous ways. For over thirty years his research, writings, and ideas were shared and discussed with his close friend Jeff Perry.

As an individual, Ted Allen attracted a wide circle of friends. He presented himself in a humble and homespun way, he was thoughtful and generous in manner, he had a wonderful sense of humor, and he took time to undertake many daily acts of caring and consideration. He was true and loyal to his friends, but always in a principled and forthright way. In many respects, he was a model of the true working-class intellectual. He lived what he preached and he was rooted deep in the working class. He challenged the division between thinkers and laborers, his work was connected to labor and anti- white-supremacist activists and actions, he was disciplined and persistent in his intellectual work, and he was principled in his politics. His life was dedicated to radical social change and he remained true to the course.

Allen's The Invention of the White Race, as well as his other pamphlets, articles, letters, talks, and unpublished manuscripts on the theory and practice of white supremacy in United States history have influenced several generations of anti-white supremacist and labor scholars and activists. They have also impacted a wide range of academic fields including history, sociology, politics, and legal, cultural, and literary studies. His most recent work includes an almost completed book length manuscript, "Toward a Revolution in Labor History" and an article submitted for publication only weeks before his death which focused on the individual and the collective and addressed theoretical problems in the socialist movement.

Theodore Allen was pre-deceased by his elder sister Eula May of Harrisonburg, Va. He is survived by his elder brother Tom, his siblings' families, his stepson Michael Strong, his companion in the 1970s and close friend Linda Vidinha, and by many friends, relatives, neighbors, co-workers, and people influenced by his work.

His literary works have been left to his literary executor, Jeffrey B. Perry, and plans are underway to publish and disseminate his writings and to place the Theodore W. Allen Papers with a repository.

A "Theodore W. Allen Scholar Program" has been established in honor of his "pioneering work" on race and class as a "politically engaged independent scholar and public intellectual." That program, under the auspices of the Center for Working Class Life of the Economics Department of the State University of New York, Stony Brook, 11794-4384, 631-632-7536 (Michael Zweig, Director), will support scholarship and public presentations exploring the intersections of race and class. Tax-deductible contributions to the Fund may be made out to "Stony Brook Foundation" and marked "for Theodore William Allen Scholar Program."

Two commemorative events are being scheduled in Ted Allen's memory. In the early spring, his ashes (as per his request) will be spread over that area "three miles up country" from West Point, Virginia where the "foure hundred English and Negroes in Arms" demanded their freedom in 1676.

The second activity, planned for June 18, 2005, from 1 to 4 p.m. in the community auditorium of the Brooklyn Public Library, Grand Army Plaza, Brooklyn, will commemorate Ted's life and work and include testimony from family and friends who desire to speak on his life, work, and influence.

A two-part "Summary of the Argument of The Invention of the White Race" by Theodore W. Allen can be found in Cultural Logic at"Summary of the Argument of The Invention of the White Race (Part 1) and "Summary of the Argument of The Invention of the White Race (Part 2).

Among Ted's many well wishers during his recent battle were:

Read More

Allen, an ardent opponent of white supremacy, spent much of his last forty years researching the role of white supremacy in United States history and examining records of colonial Virginia as he documented and analyzed the development of the "white race" in the latter part of the seventeenth century. His main thesis, that the "white race" developed as a ruling class social control formation in response to labor unrest as manifest in Bacon's Rebellion of 1676-77, was first articulated in February 1974 in a talk he delivered at a Union of Radical Political Economists meeting in New Haven. Versions of that talk were published in 1975 in Radical America

In the 1960s "Ted" Allen significantly influenced the direction of the student movement and the new left with an article entitled "Can White Radicals Be Radicalized?" which developed the argument that white supremacy, reinforced among European Americans by the "white skin privilege," was the main retardant of working class consciousness in the United States and that efforts at radical social change should direct principal efforts at challenging the system of white supremacy and urging "repudiation of white skin privilege" by European Americans.

Allen was in the forefront in challenging phenotypical (physical appearance-based) definitions of race, in challenging "racism is innate" arguments, in challenging theories that the working class benefits from white supremacy, in calling attention to the crucial role of the buffer social control group in racial oppression, in documenting and analyzing the development of the "white race" in the latter part of the seventeenth century, and in clarifying how "this all-class association of European-Americans held together by 'racial' privileges conferred on laboring class European-Americans relative to African-Americans--[has served] as the principal historic guarantor of ruling-class domination of national life" in the United States. These contributions differentiate his work from many writers in the rapidly growing white race as "a social and cultural construction" ranks, which his writings helped to spawn.

In The Invention of the White Race Allen focused on Virginia, the first and pattern-setting continental colony. He emphasized that "When the first Africans arrived in Virginia in 1619, there were no white people there" and he added that he found "no instance of the official use of the word 'white' as a token of social status before its appearance in a Virginia law passed in 1691." He also found, similar to historian Lerone Bennett, Jr., that throughout most of the seventeenth century conditions for African-American and European-American laborers and bond-servants were very similar. Under such conditions solidarity among the laboring classes reached a peak during Bacon's Rebellion: the capitol (Jamestown) was burned; two thousand rebels forced the governor to flee across the Chesapeake Bay and controlled 6/7 of Virginia's land; and, in the latter stages of the struggle, "foure hundred English and Negroes in Arms" demanded their freedom from bondage.

To Allen, the social control problems highlighted by Bacon's Rebellion "demonstrated beyond question the lack of a sufficient intermediate stratum to stand between the ruling plantation elite and the mass of European-American and African-American laboring people, free and bond." He then detailed how, in the period after Bacon's Rebellion the white race was invented as "a bourgeois social control formation in response to [such] laboring class unrest." He described systematic ruling class policies, which extended privileges to European laborers and bond-servants and imposed and extended harsher disabilities and blocked normal class mobility for African-Americans. Thus, for example, when African-Americans were deprived of their long-held right to vote in Virginia and Governor William Gooch explained in 1735 that the Virginia Assembly had decided upon this curtailment of the franchise in order "to fix a perpetual Brand upon Free Negros & Mulattos," Allen emphasized that this was not an "unthinking decision"! "Rather, it was a deliberate act by the plantation bourgeoisie; it proceeded from a conscious decision in the process of establishing a system of racial oppression, even though it meant repealing an electoral principle that had existed in Virginia for more than a century."

For Allen, "The hallmark, the informing principle, of racial oppression in its colonial origins and as it has persisted in subsequent historical contexts, is the reduction of all members of the oppressed group to one undifferentiated social status, beneath that of any member of the oppressor group." The key to understanding racial oppression, he wrote, is the social control buffer -- that group in society, which helps to control the poor for the rich. Under racial oppression in Virginia, any persons of discernible non-European ancestry in colonial Virginia after Bacon's Rebellion were denied a role in the social control buffer group, the bulk of which was made up of working-class "whites." In contrast, Allen explained, in the Caribbean "Mulattos" were included in the social control group and were promoted into middle-class status. For him, this was "the key to the understanding the difference between Virginia ruling-class policy of 'fixing a perpetual brand' on African-Americans" and "the policy of the West Indian planters of formally recognizing the middle-class status 'colored' descendant (and other Afro-Caribbeans who earned special merit by their service to the regime)." The difference "was rooted in the objective fact that in the West Indies there were too few laboring-class Europeans to embody an adequate petit bourgeoisie, while in the continental colonies there were too many to be accommodated in the ranks of that class." (In 1676 in Virginia, for example, there were approximately 6,000 European-American bond-laborers and 2,000 African-American bond-laborers.)

In 1996, on radio station WBAI in New York, Allen discussed the subject of "American Exceptionalism" and the much-vaunted "immunity" of the United States to proletarian class-consciousness and its effects. His explanation for the relatively low level of class consciousness was that social control in the United States was guaranteed, not primarily by the class privileges of a petit bourgeoisie, but by the white-skin privileges of laboring class whites; that the ruling class co-opts European-American workers into the buffer social control system against the interests of the working class to which they belong; and that the "white race" by its all-class form, conceals the operation of the ruling class social control system by providing it with a majoritarian "democratic" facade.

Theodore William Allen, the third child (after a sister Eula May and brother Tom) of Thomas E. and Almeda Earl Allen was born into a middle-class family August 23, 1919, in Indianapolis, Indiana. His father was a sales manager and his mother a housewife. In 1929 the family moved to Huntington, West Virginia, where, Ted was, in his words, "proletarianized by the Great Depression." He attended college for a couple of days after high school, but, because he didn't believe that setting encouraged independent thought, he didn't think it was for him and didn't go back.

At age 17 he joined the American Federation of Musicians (Local 362) and served as its delegate to the Huntington Central Labor Union, AFL. He continued work in the trade union movement as a coal miner in West Virginia for three years until he was forced to leave because of a back injury. During that period he belonged to United Mine Worker locals 5426 (Prenter, West Virginia), 6206 (Gary, West Virginia) where he was an organizer and Local President, and 4346 (Barrackville, West Virginia). He also was co-organizer of a trade union organizing program for the Marion County West Virginia Industrial Union Council, CIO.

In 1938 Allen married Ruth Voithofer, one of eleven children in a coal-mining family, whom he first met in 1934. Ruth was active in organizing and educational work among mining families and women and, beginning in 1942, was a prominent organizer for the United Electrical Workers Union. They separated in the mid-1940s and Ruth Newell (her name after re-marrying) died in 1999.

In 1948 Ted moved to New York. He had joined the Communist Party in the 1930s and, after coming to New York, he taught classes in economics at the Party's Jefferson School at Union Square in Manhattan (1949-56). He was also active in community, civil rights, trade union, and student organizing work; he worked in a factory, as a retail clerk, as a mechanical design draftsman, as an elevator operator, and as a junior high school math teacher at the Grace Church School in Greenwich Village.

In the 1950s Ted married Marie Strong, a poet, and became stepfather to her son, Michael. In the late 1950s the Communist Party went through major repression and internal struggle and Ted left the Party in order to help establish a new organization the Provisional Organizing Committee to Reconstitute the Communist Party (POC). In this period he wrote a number of economic and political articles on the economic situation in the United States and he argued that neither United States nor Latin American workers benefited from imperialism. In 1962 Marie died tragically and Ted, suffering greatly from her loss, discontinued work with the POC and traveled to England and Ireland.

By the mid 1960s, back in Brooklyn, and increasingly affected by the political climate marked by the growing civil rights movement, struggles for national liberation and socialism, and the Vietnam War, Allen set about taking a fresh look at the world and at his former beliefs. Nothing would be sacred. Though his formal education had ended with high school, he was a trained economist, he read widely in history, politics, literature, and the sciences, and he had a probing and analytical mind -- all of which would serve him well in the work ahead.

Drawing on the insights of W. E .B. Du Bois in Black Reconstruction on the blindspot of America, which he paraphrased as "the white blindspot," Allen began work on a historical study of three crises in United States history in which there were general confrontations of the forces of capital and those from below -- the crises of The Civil War and Reconstruction, the Populist Revolt of the 1890s, and the Great Depression of the 1930s. His work focused on the role of the theory and practice of white supremacy in shaping those outcomes. He worked together with his friend, the late Esther Kusic, and his work influenced another friend, Noel Ignatin [Ignatiev]. Together, Ignatin and Allen provided the copy for an influential pamphlet containing both "White Blindspot," under Ignatin's name, and Allen's article "Can White Radicals Be Radicalized."

Allen argued against what he referred to as the current consensus on U.S. labor history -- one which attributed the low level of class consciousness among American workers to such factors as the early development of civil liberties, the heterogeneity of the work force, the "safety valve" of homesteading opportunities in the West, the ease of social mobility, the relative shortage of labor, and the early development of "pure and simple trade unionism." He emphasized that each of these rationales had to be reinterpreted in terms of white supremacy, that white supremacy was reinforced by the white-skin privilege of white workers, and "that the white-skin privilege does not serve the real interests of the white workers."

The pamphlet, which issued a call to action -- "to repudiate the white-skin privilege" -- was published by the SDS-affiliated Radical Education Project and it had immediate effect on the left. It sharply posed the issues of how to fight white supremacy and whether, or not, that fight was in the interest of "white" workers. It also set the terms of discussion and debate for many activists within SDS.

Allen developed the analysis in his article into a still unpublished book-length manuscript entitled "The Kernel and the Meaning" (1972). It was then, in 1972, in the course of this work, that he became convinced that the problems related to white supremacy couldn't be resolved without a history of the plantation colonies of the 17th and 18th century. His reasoning was clear -- white supremacy still ruled in the United States more than a century after the abolition of slavery and the reasons for that had to be explained. He proceeded to search for a structural principle that was essential to the social order based on slave labor in the continental plantation colonies and still was essential to late twentieth-century America's social order based on wage-labor.

Over the next twenty years Allen did extensive primary research in colonial Virginia records (and his unpublished transcripts of this work, with his eye for the conditions of labor, are another of his important historical contributions). In this period he generated other unpublished book-length manuscripts including "The Genesis of the Chattel-Labor System in Continental Anglo-America" and "The Peculiar Seed," both of which dealt with the early 17th-century development of chattel bond-servitude in Virginia, under which workers could be bought and sold like property. (This chattelization of labor was done primarily among European American workers at first.)

When the first volume of The Invention of the White Race appeared it drew on, and challenged, the work of some of America's leading colonial historians including Winthrop Jordan and Edmund S. Morgan. It offered important theoretical and historical insights in the struggle against white supremacy when it challenged the two major arguments which tend to undermine the struggle against white supremacy in the working class -- the notion that racism is innate (as suggested by Jordan's "unthinking decision" explanation) and the notion that European-American workers benefit from racism (as suggested by Morgan's "there were too few free poor on hand to matter").

Allen challenged these ideas with his factual presentation and analysis, by providing a comprehensive alternate explanation, and by skillfully drawing on examples from Ireland (where a religio/racial oppression existed under the Protestant Ascendancy) and the Caribbean (where a different social control formation was developed based on promotion of "Mulattos" to petit-bourgeois status). He concluded that the codifications of the Penal Laws of the Protestant Ascendancy in Ireland and the slave codes of white supremacy in continental Anglo-America presented four common defining characteristics of those two regimes: 1) declassing legislation, directed at property-holding members of the oppressed group; 2) the deprivation of civil rights; 3) the illegalization of literacy; and 4) displacement of family rights and authorities. This understanding of racial oppression led him to conclude that a comparative study of "Protestant Ascendancy" in Ireland, and "white supremacy" in continental Anglo-America (in both its colonial and regenerate United States forms) demonstrates that racial oppression is not dependent upon differences of "phenotype."

While working on The Invention of the White Race Allen taught as an adjunct history instructor at Essex County Community College in Newark, NJ, and worked several years each on the staff of the Brooklyn Museum, as a postal mail handler in Jersey City, NJ, and as a librarian at the Brooklyn Public Library. Constantly at the edge of poverty his scholarship was remarkable for its dedication and tenacity in the face of great personal difficulties. During this period his research in Virginia was facilitated by the generosity of Ed Peeples and his family in Richmond and his work in Brooklyn was encouraged by his former companion and close friend Linda Vidinha, her family and her companion Marsha Rosenthal, and a number of other close friends and neighbors who supported his efforts in numerous ways. For over thirty years his research, writings, and ideas were shared and discussed with his close friend Jeff Perry.

As an individual, Ted Allen attracted a wide circle of friends. He presented himself in a humble and homespun way, he was thoughtful and generous in manner, he had a wonderful sense of humor, and he took time to undertake many daily acts of caring and consideration. He was true and loyal to his friends, but always in a principled and forthright way. In many respects, he was a model of the true working-class intellectual. He lived what he preached and he was rooted deep in the working class. He challenged the division between thinkers and laborers, his work was connected to labor and anti- white-supremacist activists and actions, he was disciplined and persistent in his intellectual work, and he was principled in his politics. His life was dedicated to radical social change and he remained true to the course.

Allen's The Invention of the White Race, as well as his other pamphlets, articles, letters, talks, and unpublished manuscripts on the theory and practice of white supremacy in United States history have influenced several generations of anti-white supremacist and labor scholars and activists. They have also impacted a wide range of academic fields including history, sociology, politics, and legal, cultural, and literary studies. His most recent work includes an almost completed book length manuscript, "Toward a Revolution in Labor History" and an article submitted for publication only weeks before his death which focused on the individual and the collective and addressed theoretical problems in the socialist movement.

Theodore Allen was pre-deceased by his elder sister Eula May of Harrisonburg, Va. He is survived by his elder brother Tom, his siblings' families, his stepson Michael Strong, his companion in the 1970s and close friend Linda Vidinha, and by many friends, relatives, neighbors, co-workers, and people influenced by his work.

His literary works have been left to his literary executor, Jeffrey B. Perry, and plans are underway to publish and disseminate his writings and to place the Theodore W. Allen Papers with a repository.

A "Theodore W. Allen Scholar Program" has been established in honor of his "pioneering work" on race and class as a "politically engaged independent scholar and public intellectual." That program, under the auspices of the Center for Working Class Life of the Economics Department of the State University of New York, Stony Brook, 11794-4384, 631-632-7536 (Michael Zweig, Director), will support scholarship and public presentations exploring the intersections of race and class. Tax-deductible contributions to the Fund may be made out to "Stony Brook Foundation" and marked "for Theodore William Allen Scholar Program."

Two commemorative events are being scheduled in Ted Allen's memory. In the early spring, his ashes (as per his request) will be spread over that area "three miles up country" from West Point, Virginia where the "foure hundred English and Negroes in Arms" demanded their freedom in 1676.

The second activity, planned for June 18, 2005, from 1 to 4 p.m. in the community auditorium of the Brooklyn Public Library, Grand Army Plaza, Brooklyn, will commemorate Ted's life and work and include testimony from family and friends who desire to speak on his life, work, and influence.

A two-part "Summary of the Argument of The Invention of the White Race" by Theodore W. Allen can be found in Cultural Logic at

Among Ted's many well wishers during his recent battle were:

Sean, Donna, and Dylan Ahern

Thomas E. Allen

Thomas E. (Dobby) and Dorothy Allen

Irving and Mildred Appelbaum

Dennis and Ruth Blunt

Peter Bohmer

Evie, Gene, and Nadja Bruskin

Florence, Remco, Uchenna, and Obina Van Capeleeven

Rosemarie Cavagnaro

Connie and Bill Coleman

Gerry Colby

Lynn and John Dambeck

Durand, Priscilla, & Luke Daniel

Carl Davidson

Lee and May Davenport

Barbara Denlinger

Mary DiGregorio

Dilmeran Dunham

David Finkel

Bill Fletcher

Anamaria Flores

Tami Gold

Philip Harper

Becky and Perri Hom

Anne and Charles Johnson

Barbara Johnson

Stella Jones

Bob Kirkman

Beth Lyons

Pamela McKenzie

Leon Moultrie

Gerry and Carolyn Mosseller

Greg Myerson

Maggie Paul

Dennis O'Neil

Kay Osborn

Carol Patti

Chad Pearson

Eva and John Pellegrini

Edward, Karen, and Camille Peeples

Jeff Perry

Greg and Linda Reight

Cecily Rodriguez

Gilberto Rodriguez

Linda Roma

Marcy Rosenthal

Arlene and Spencer Rothenhauser

Yvette, Christopher, and Gabriel Roussel

Frank and Stacy Saavedra

Andrea Schneer

Jonathan Scott

Vicki and Bob Shand

Dave Siar

David Slavin

Christina Starobin

Michael Strong

Vivian Todini

Chris Tsakos

Linda Vidinha

Mary Vidinha

Stella Winston

Joan Zimmerman

Michael Zweig

Read More